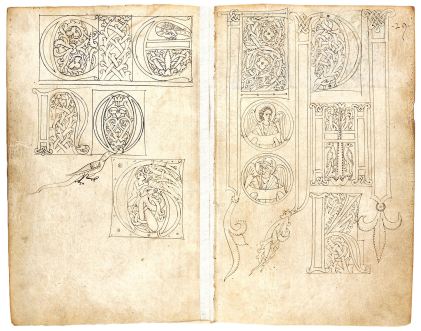

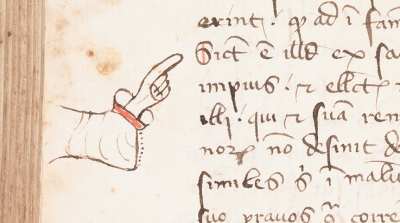

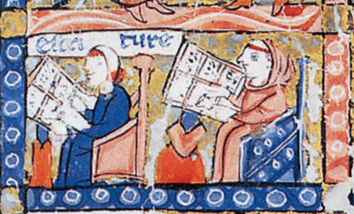

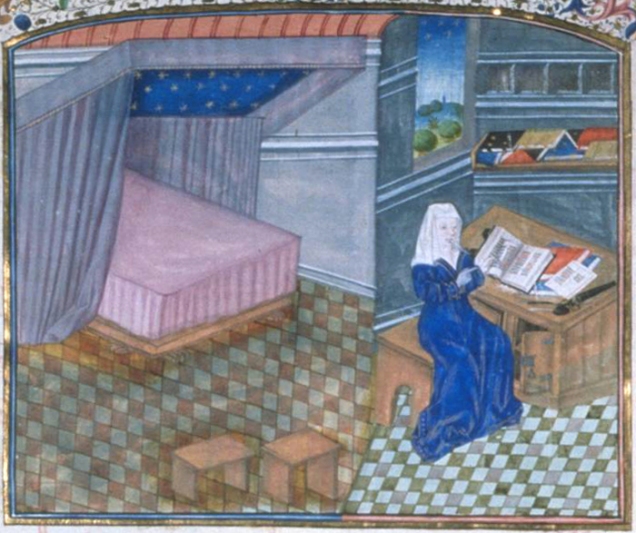

Medieval readers, especially studious ones, must have cursed their desks from time to time. It is not easy to manage desk space when working with often large and clunky medieval books. Scribes and translators developed work-arounds for these space issues, as I have shown in a blog post on medieval desktops. Scribes would place two desk surfaces stacked vertically, one for the book that was copied from, the other for the copy (image here). In contrast, translators would sometimes position two surfaces next to one another, one presumably for the original text, the other for the translation (see the striking images here and here). Readers, however, faced bigger challenges, since many needed more than two books open at the same time, which produced clutter and frantic searches for particular information. Figure 1 shows the French author Christine de Pisan, who is often shown while working in her study (here is an interesting article on the iconography), sitting behind a desk cluttered by books.

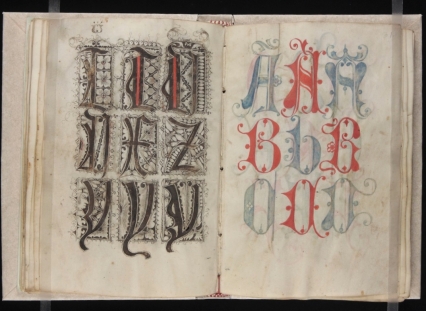

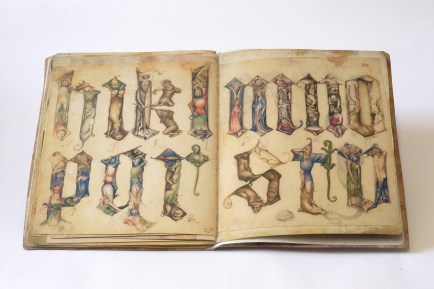

Near the end of the Middle Ages a device came into service that helped avid readers like Christine: the book carousel or book wheel. When precisely this device became available to medieval readers is hard to deduce, but the oldest specimens I was able to find date from the fourteenth century. While being careful of the fact that medieval images may not necessarily be a truthful depiction of reality, it appears that during this early period there are two clearly distinguishable designs available. The difference lies in the number of shelves the device was fitted with, and thus in the carousel’s capacity.

Plain design

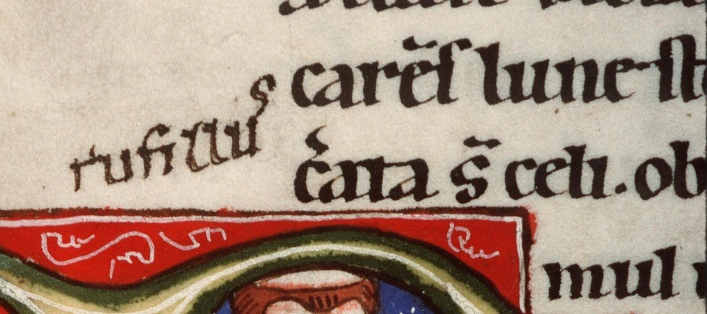

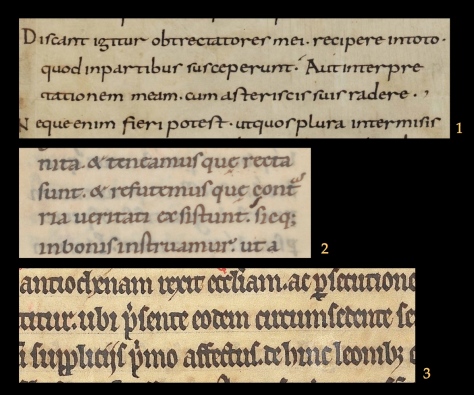

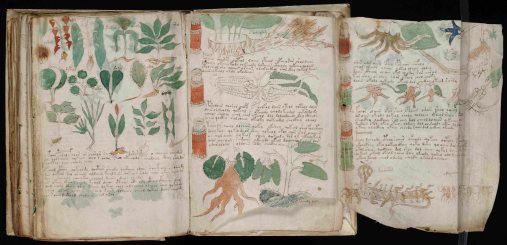

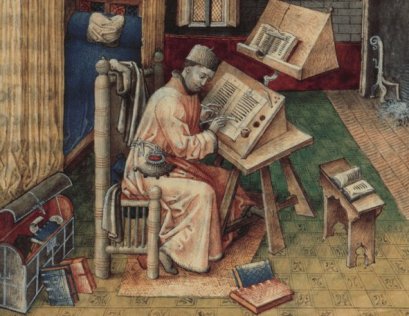

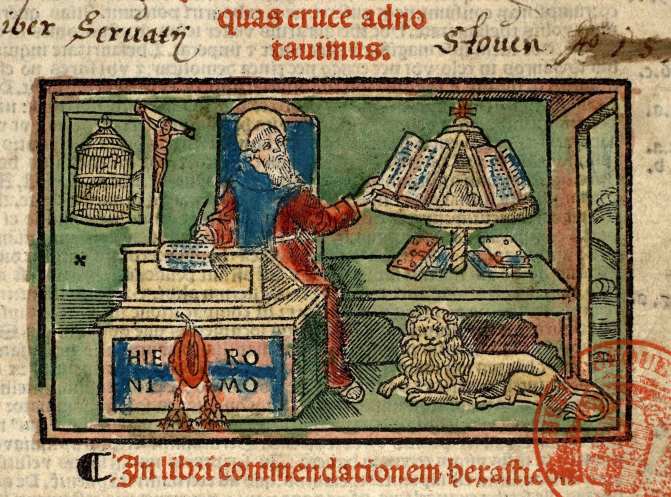

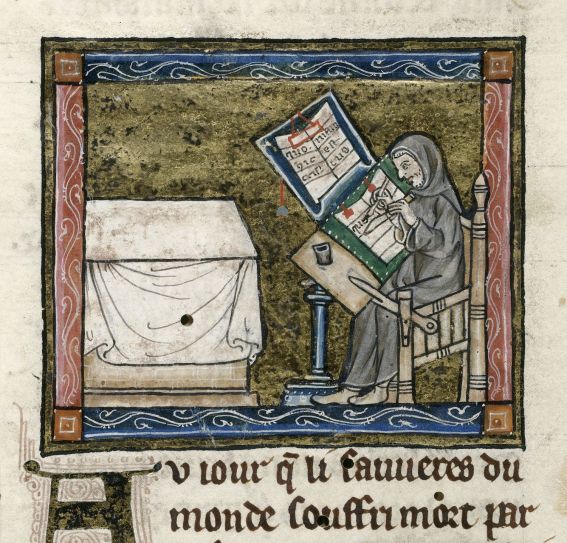

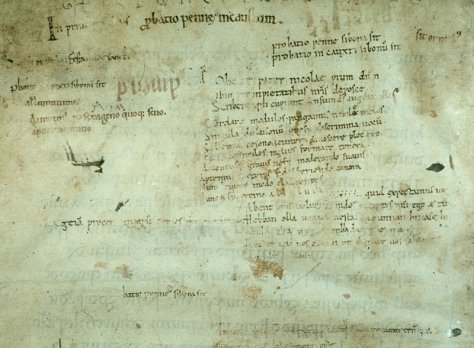

The book carousel enabled readers to have multiple books at hand, including copies that were opened to a relevant page. Among the earliest depictions are carousels shown with a single deck, providing room for no more than four to six tomes (although those with room for only two books also existed, as seen here). Early depictions of this “plain” model are seen in Figure 2 (from 1383) and Figure 3 (from c. 1400). These book wheels share some striking features. One is that the carousel stands on top of the desk, usually at the far end, where it is out of the way. This is most clearly observed in the depiction of a writing Cicero in the Bodleian Library manuscript (Figure 2). Here the carousel is placed in arm’s reach and contains various open books: the author merely has to turn the platform – carefully! – to consult them. Additional books are present in a book cupboard nearby. These would presumably be placed on the wheel when they were needed.

A similar scene is observed in Figure 3, which is found in a copy of Petrarch’s De viris illustribus kept in the University Library in Darmstadt. Here, too, an author is seen at work with a book wheel nearby. This carousel is placed on the desk, although the image shows this less clearly. Here the author is reading, not writing: Petrarch uses both hands to thumb through the book as if looking for certain information. More sources are nearby, placed on the book wheel, which can be consulted simply by reaching over. As in Figure 2, an open book is present on the platform; additionally, a red copy with the clasps unhooked lies at the ready. However, the platform also holds a roll, by the looks of it, as well as loose pieces of paper. This carousel is clearly in heavy use!

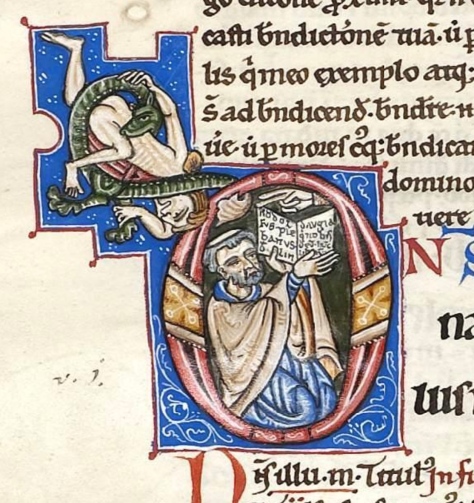

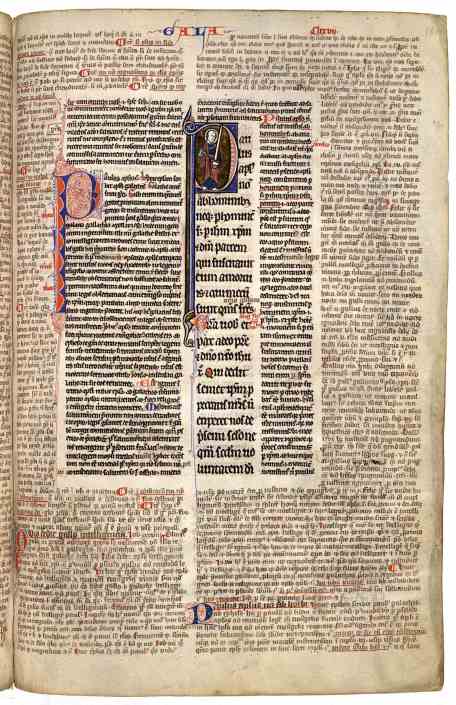

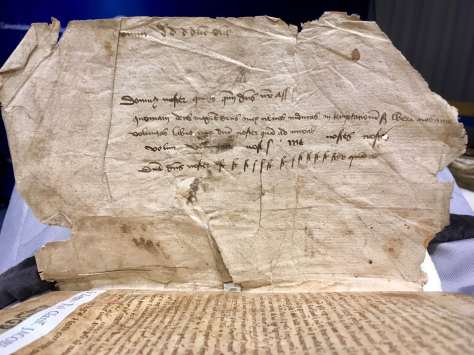

The images shown so far share two striking features: the book carousel appears to consist of a single platform and the device was small enough to place on top of one’s desk. (Curiously, some carousels were designed with an arm, enabling the user to “swing” the platform closer, as this example shows.) This relatively plain design continued until the end of the medieval period, and even beyond. Figure 4 shows a woodcut from a late-fifteenth-century incunabulum (an early printed book) containing a bible with commentary (here is another example from an incunabulum). Jerome, that revered bible translator, is shown sitting behind a single-platform book wheel consulting various source texts. While this scene is very appropriate given that the Church Father is known to have consulted a great deal of sources for the production of his Vulgate Bible, including Hebrew manuscripts, it clearly concerns medievalization of an ancient scene.

More sophisticated designs

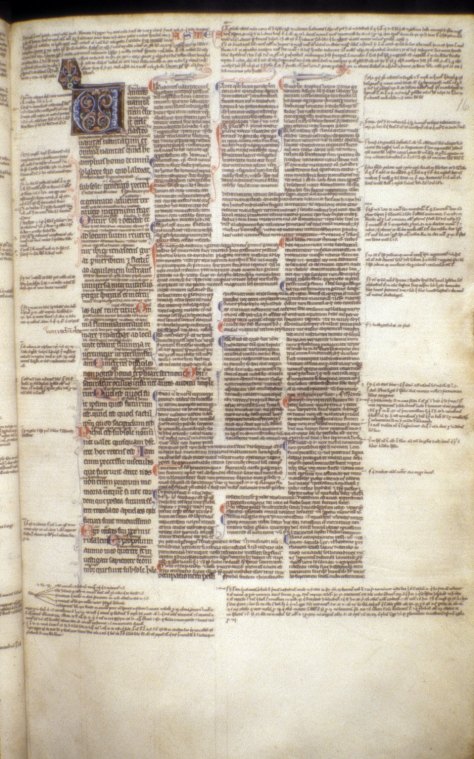

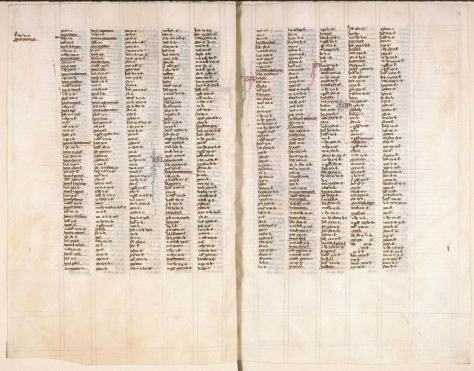

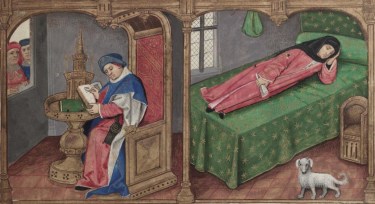

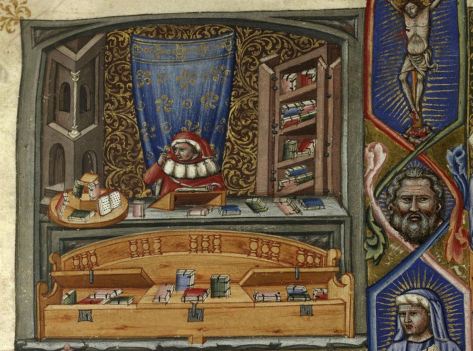

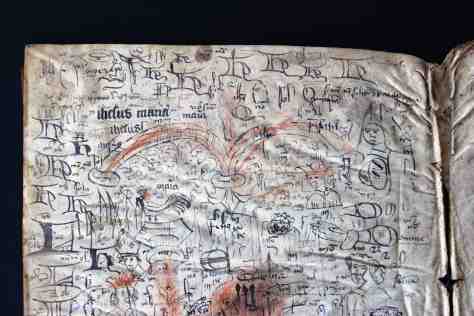

There were also more sophisticated carousels available to the medieval reader: some book wheels were fitted with two rotating platforms. This seems a sensible step-up given the limited capacity that came with a single platform – note that the individuals in Figures 2-4 all have books nearby that do not fit on their carousel. Among the surviving depictions of this “double-decker” design are two from the fourteenth century (Figures 5-6). It shows that the one and two-deck designs were in use in the same century, which indicates that readers likely preferred one or the other. In other words, we do not seem to be dealing with a chronological development.

Both individuals seen in Figures 5-6 are scribes. The first in particular is very engaged with books, which are shown all around him. Not only is his desk fitted with a two-tiered book carousel, there is also a book case present behind him (note the handy fold-away doors), as well as a wooden bench that doubles as book storage. This “book bench” is fitted with locks, so that its precious contents were hidden from thieves.

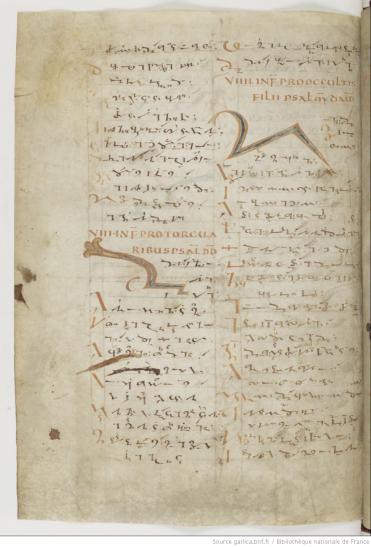

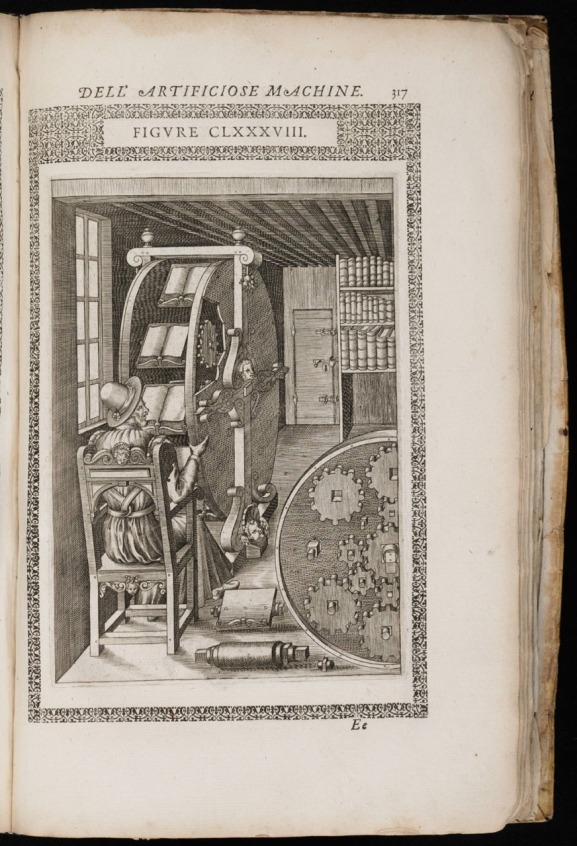

Even more sophisticated designs appeared just beyond the Middle Ages. Surviving from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are both depictions and actual specimens of book carousels that were not fitted with a horizontally turning platform, but that moved vertically. Carousels with this orientation can be fitted with a relatively high number of shelves, perhaps as many as eight or ten. In order for the books to not fall off, it was crucial that the shelves remained level as they were turning. The most famous of these is the book wheel shown in The Diverse and Artifactitious Machines of Captain Agostino Ramelli from 1588 (Figure 7). The engraving includes the complex mechanism that held the books level.

Early-modern readers also could opt to purchase (have built, presumably) a less elaborate carousel with a vertical orientation, one with a modest number of shelves, each of which fitting one or two books. The one in the Bibliotheca Thysiana in Leiden contains only four shelves (Figure 8). Its user, Johannes Thysius (d. 1653), could consult up to eight books at the same time while sitting or standing behind the machine. The mechanism that held the books level is hidden inside the sides of the carousel. Even though you’d expect the books to remain on the shelves, it is quite a sensation to see the shelves remain dead level as you turn the carousel:

Larger carousels than the ones shown here do not seem to have been around in the medieval or early-modern period. There were ways to expand the device’s capacity, however, for example by adding a stationary shelf at the foot of the carousel, or even placing the book wheel on top of a small book cupboard (here is an example). Cases like this show that book carousels may have doubled as book cases. After all, private individuals in the medieval period did not usually own a large library. The modest number of books they owned would normally fit on a book wheel with a horizontal orientation. In other words, in addition to being a handy device for studying or reading multiple books at the same time, book carousels were also most useful storage devices, keeping books safe and off the ground.

Selfies are by no means an exclusively modern phenomenon. As shown in a previous post on

Selfies are by no means an exclusively modern phenomenon. As shown in a previous post on