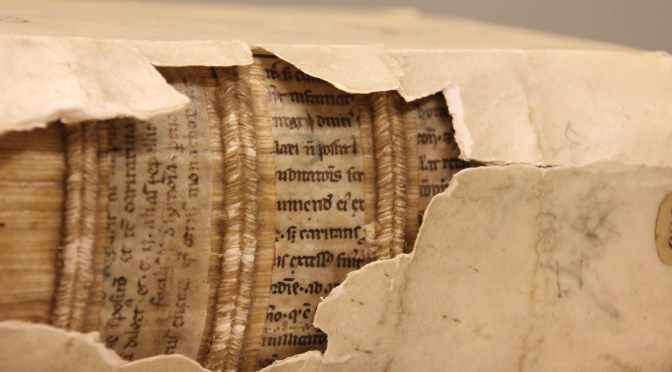

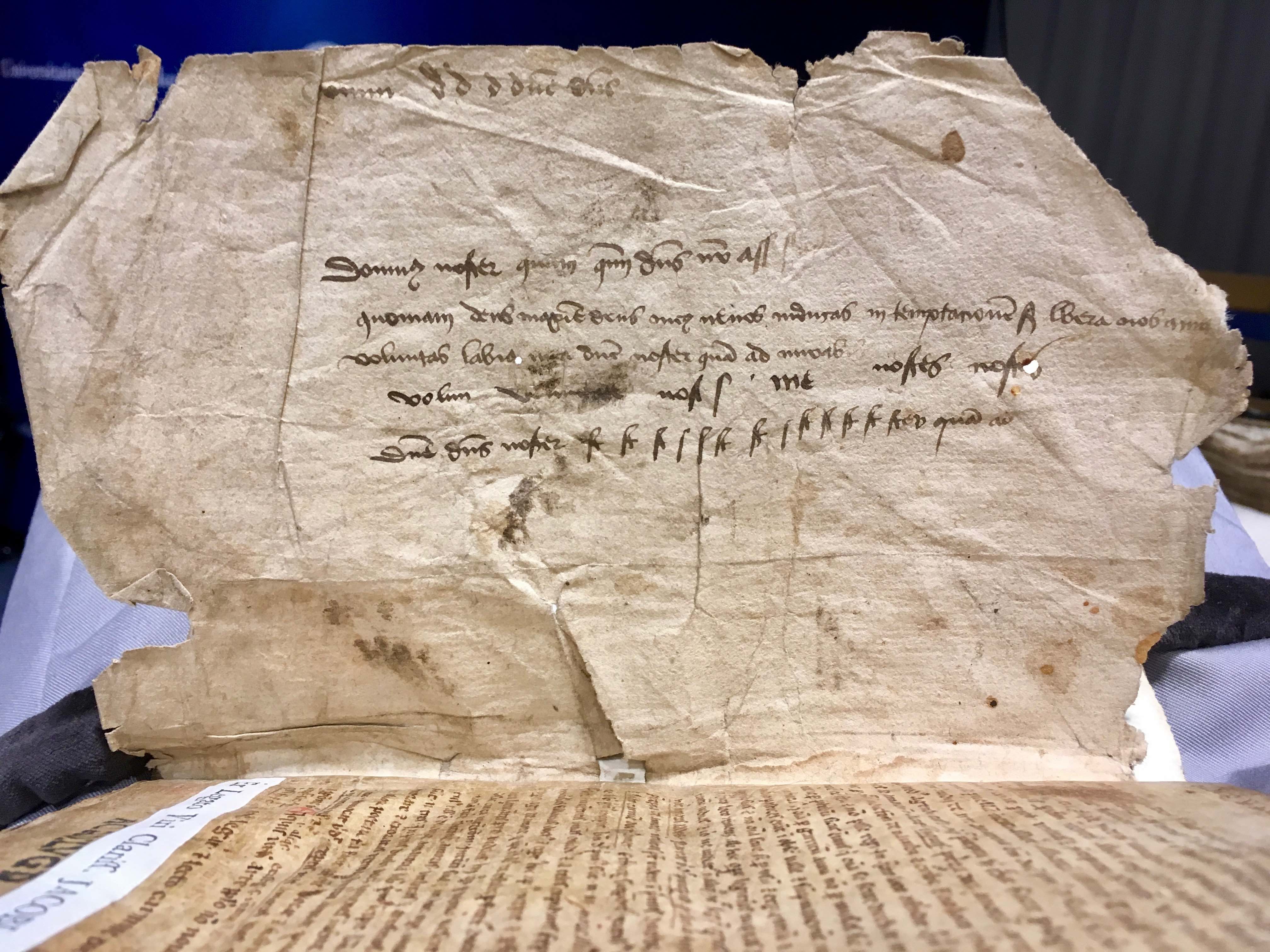

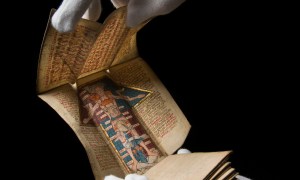

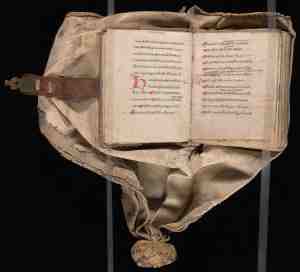

When readers in Western Europe turned their eyes to printed books, around the middle of the 15th century, handwritten books became old-fashioned, unwanted, and ultimately obsolete. Bookbinders began to disassemble medieval manuscripts and recycle their strong parchment leaves as binding materials. Thousands were systematically destroyed over the next two centuries, which is why one often encounters medieval leaves inside hidden 16th and 17th-century bindings (see image at the top, showing Leiden, UBL, 583 E 24). Elsewhere on this blog I have written about this systematic destruction (here), how to peek into the binding with MA-XRF (here), and how even today manuscripts are disassembled for profit (here). The following discusses a specific way of storing fragments and how that benefits teaching with these charming bits and pieces.

Snippets of joy

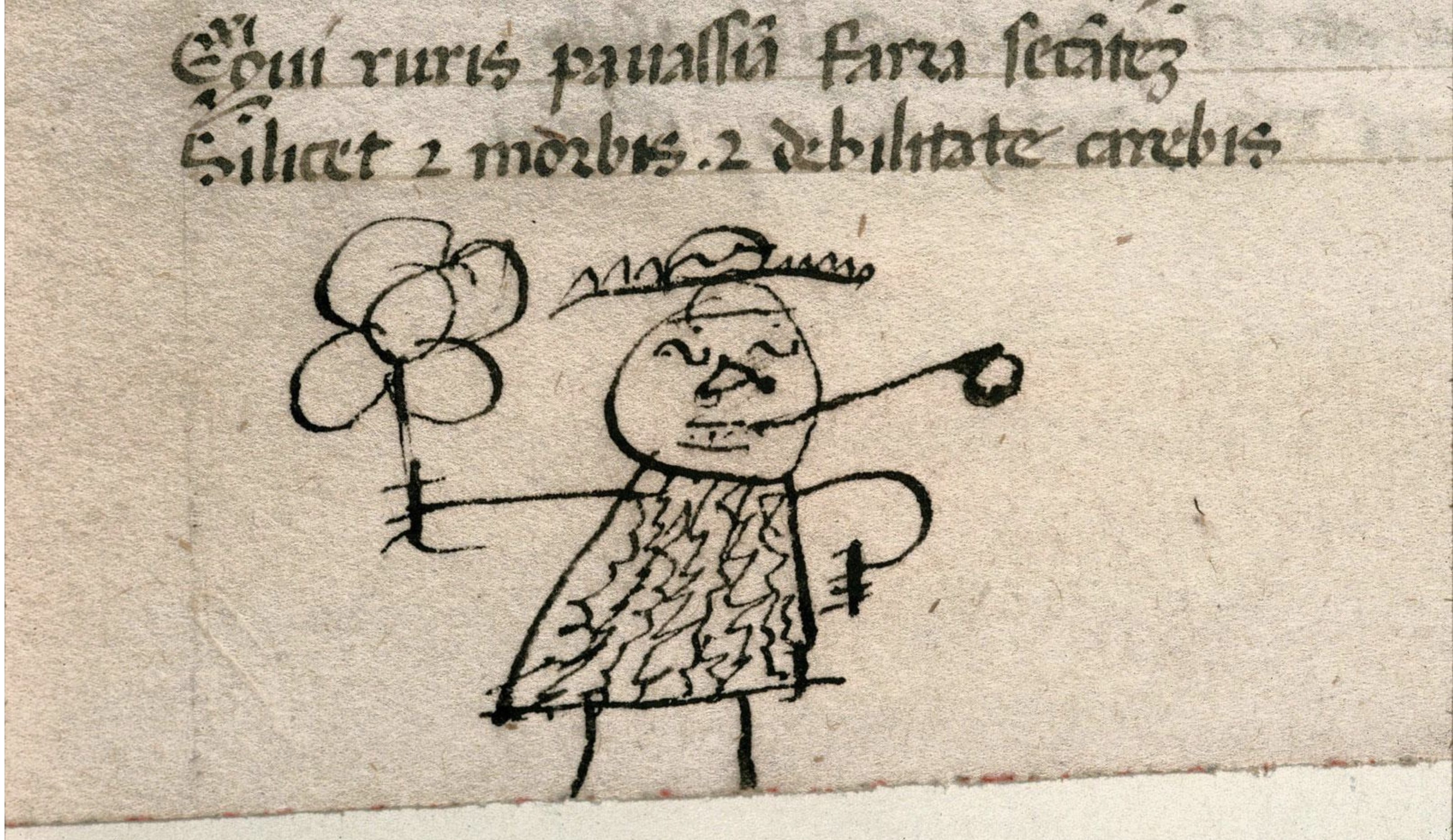

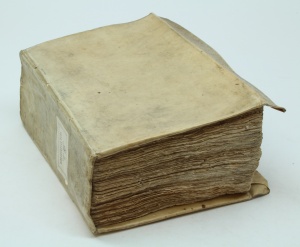

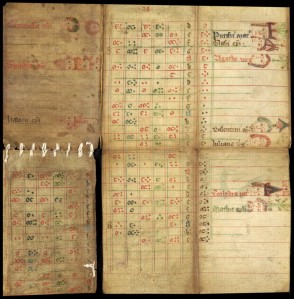

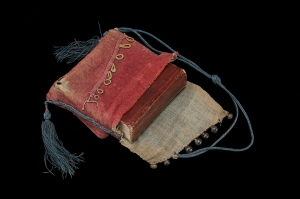

There are several reasons why fragments are perfect for teaching. Compared to the alternative – using full manuscripts – fragment leaves, and especially snippets of leaves, are less bulky and much easier to handle (Fig. 1). Fragments can withstand the curiosity of students better, especially when they are inexperienced with delicate medieval materials. A manuscript fitted in an original or early-modern binding can be awkward to handle: there is a certain tension between seeing the material details discussed in class, while ensuring the manuscript remains undamaged. Opening manuscripts fully flat is not recommended and Special Collections librarians go through great lengths to make sure that the book is supported properly during class. All this is easier with fragments, which usually comprise just a single sheet. All the while, they still show the essence of a manuscript, facilitating almost the same range of class discussion – though minus the thumbing through an actual book.

Another advantage resulting from their small size is that multiple fragments can be handled with ease at the same time, which is unpractical with full manuscripts. I often work with groups of four students positioned at a single table and with two manuscripts that table is usually full – considering other clutter, from laptops and rulers to notebooks. Having five or even ten fragments on the table is no problem and it provides each student the chance to handle a medieval “book”. Usually, such a spread of objects provides a more profound connection to the topic of discussion that day, simply because there are more examples available to show the variety of choices scribes made for each stage of production. This makes fragments ideal to discuss medieval book design principles (parchment, page layout, dimensions) and styles of handwriting (script styles, execution levels, individual style differences).

Framing the fragment

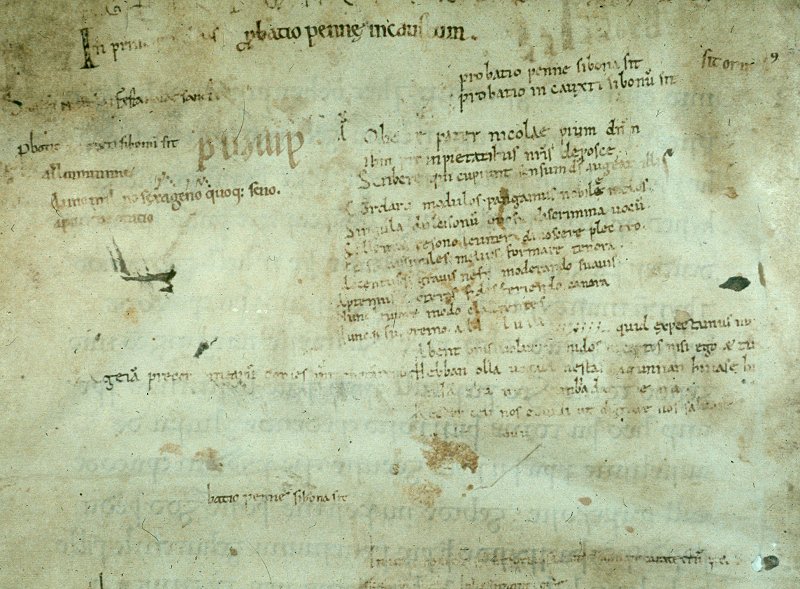

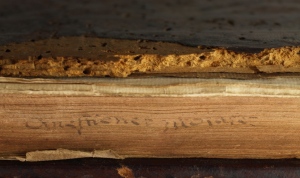

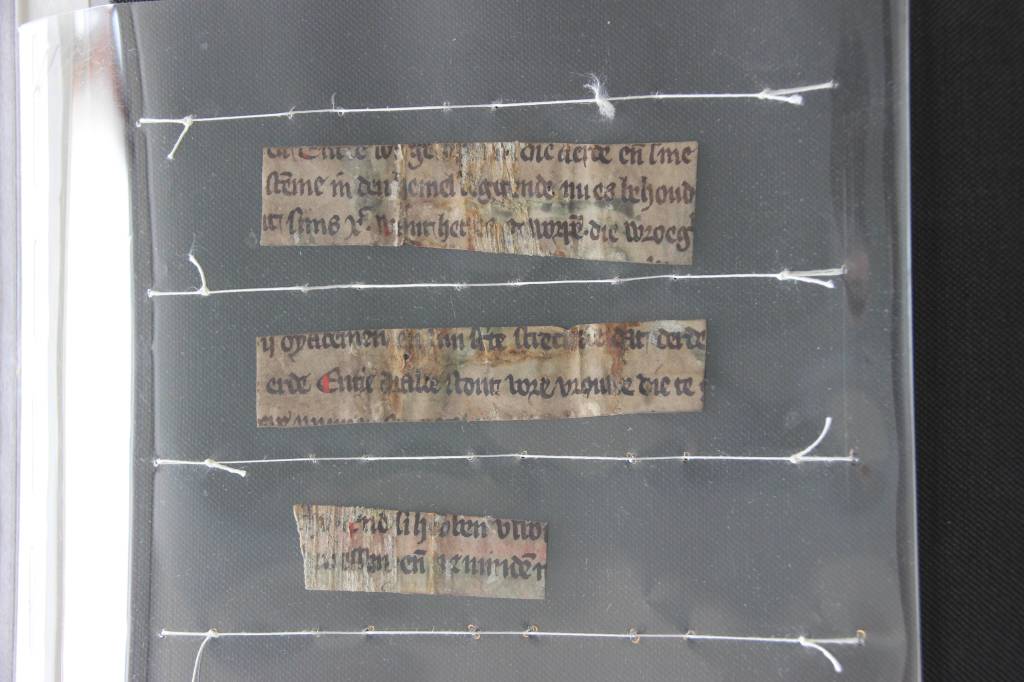

Success in the classroom depends, however, on a key factor: how they are prepared for use. Do they still need to be removed from an envelop? This is unhandy and asking for trouble, especially when putting them back in at the end of the class. Are they flattened or still curly and buckled (Fig. 1)? Flat objects show their full contents, while those with folds hide certain information. Each library has its own ways of preparing fragments for consultation. It is not uncommon to fit them in plastic, including Melinex (Fig. 2). While this provides protection, it also makes it hard to see certain details because the fragments are covered by a “mist”. Moreover, taking images can be challenging because of the reflective surface.

New solution at UBC

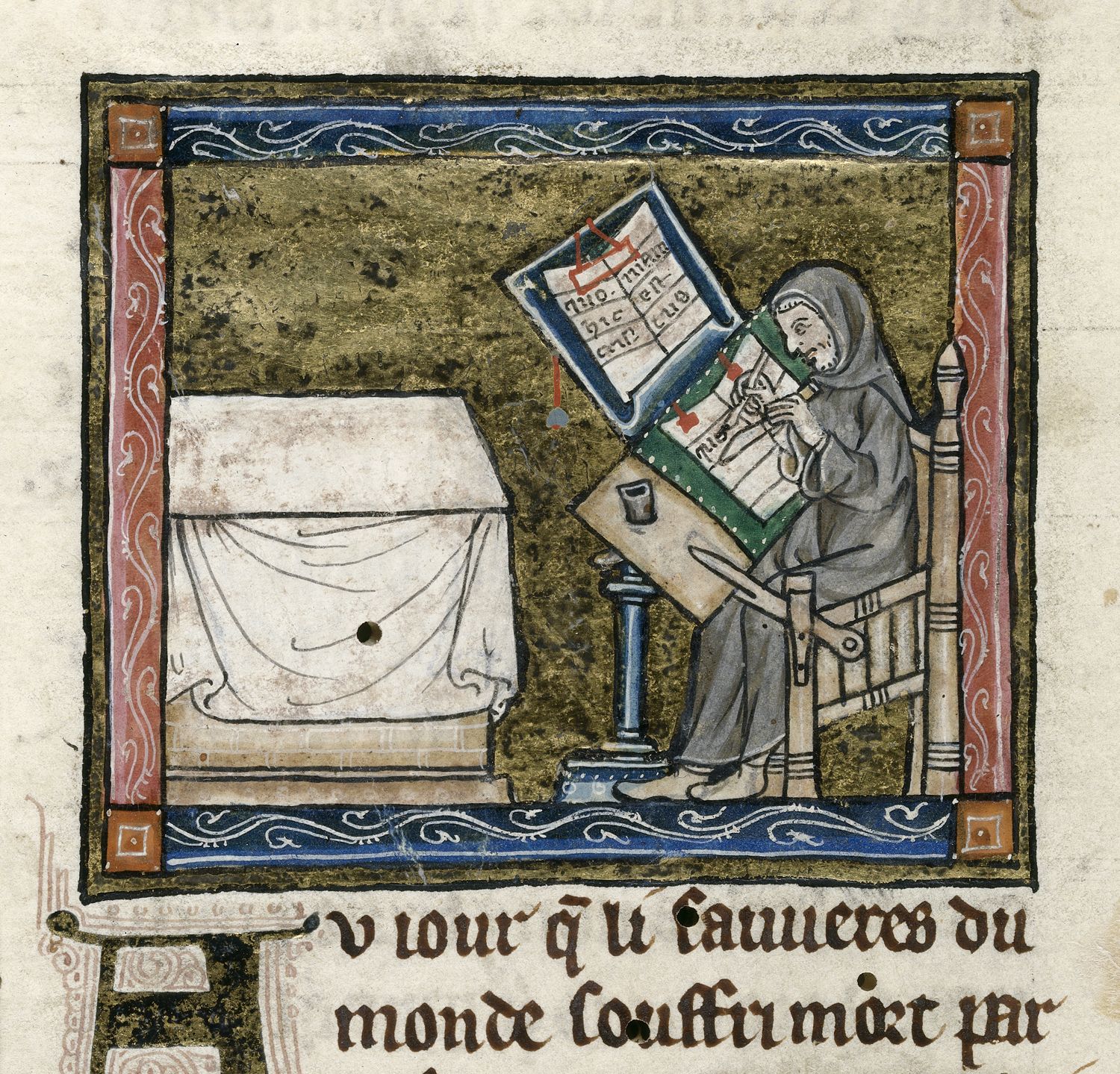

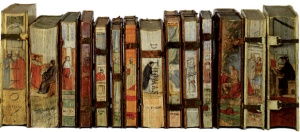

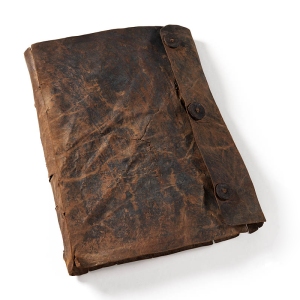

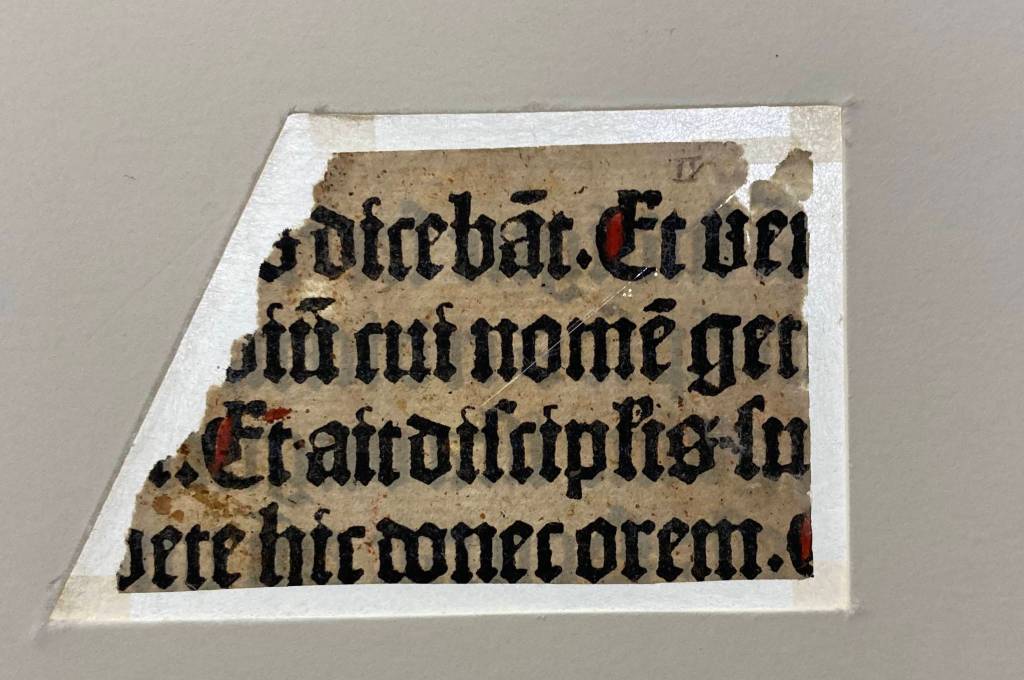

In 2022 I spent some time with the conservation specialist and her student assistant at the university library of The University of British Columbia, where I work, to figure out how to store the medieval fragment collection and how to prepare individual fragments for use in the classroom. The aim was to do so in a way that would safeguard the objects from damage (you can’t just stick them in a sturdy box, like you would with a full manuscript), while at the same time providing an optimal pedagogical experience. After initial discussions during the summer, on a snowy day in November 2022 I went down to the conservation lab to provide input on a prototype the two experts built. The solution was both simple and elegant – and also very cool-looking (Fig. 3).

Fitted in a cardboard frame with a thin insert of Japanese paper (Fig. 4), the fragment becomes a well-protected object that students can easily handle and even hold up to their eyes. There is no need to touch the actual fragment any more, or remove it from an envelop, preventing further wear and tear. At the same time, the surface is still clearly visible (much more so than in Fig. 2). For storage, this design is ideal too. One box can fit a variety of fragments, all fitted in the same size frame (the idea is to have two or three standard cardboard sizes, matching the boxes they will end up in). The framed fragment is subsequently fitted in a firm plastic folder for added protection; these folders will have an insert in which a description of the item can be fitted, which some of my students are doing as Directed Studies projects.

While UBC may not the first to frame its fragments in this way, it is the first time I have worked with this elegant solution. It makes teaching with the often unwieldy materials even more of a delight, also knowing that the delicate materials are safe. Moreover, it makes life easier for librarians too, as they can simply take a box into the seminar room and put the folders of fragments I requested on the tables. Students, in turn, have everything they need at their finger tips. Not just the actual fragment, but also a description and other materials that relate to the fragment in question, such as older storage envelops with notes. Framed fragments enable us to conveniently observe destroyed books from up close, while it improves their use in the classroom and chances for long-term survival.