I love the last page of the medieval book. Not because it means that my research of a particular manuscript is almost completed, but because the last page often provides information pertaining to the origins of the object – information not normally found elsewhere in the manuscript. This post, which discusses some of this information, is devoted to the last text page of a manuscript as well as the last physical page of the book – which are, perhaps surprisingly, not usually the same thing.

The Last Page of the Text

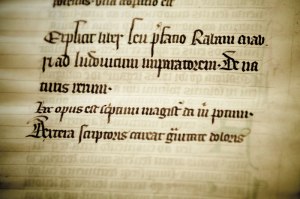

The last page of the text was a podium where the scribe could state information about himself and the circumstances of the book’s production. While few scribes seized this opportunity (about one in seven do say something), such added information, collected in what we call a “colophon”, can enrich our knowledge of a manuscript considerably. Some colophons provide a glance into the reality of the scriptorium or urban workshop, where a scribe toils over a piece of parchment. Well known are colophons that state such cries as “Please give me a drink!” or “Let my right hand be free from pain!” (see Fig. 1 and this MedievalFragments post).

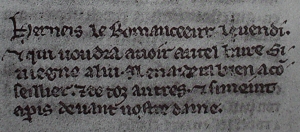

More telling are colophons where a scribe lifts the veil and allows us to peek into his or her working space. The Paris artisan Herneis states on the last page of a book he copied: “If someone else would like such a handsome book, come and look me up in Paris, across from the Notre Dame cathedral” (see Fig. 2 and this MedievalFragments post). There are other cases where a commercial scribe advertises his work. One from mid-fifteenth-century Holland copied the same book up to eight times (the historical books of the Old Testament), showing that his labor is a commercial enterprise. At the end of one of these he writes: “If there is somebody who would like a copy of the New Testament, I would be happy to provide it for payment, because it is beautiful” (Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 1006, fol. 455r).

While Herneis in Paris was spamming a general audience, telling them where to go for a good book, the anonymous scribe in Holland was likely addressing the individual for whom he just copied the Old Testament. When the reader got to the end of the last page, he stumbled into this not-so-subtle recommendation for more good stuff – not unlike what happens when you search for a good read on Amazon: “If you like that book, you will love this one!”

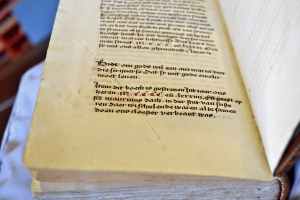

As exciting as these examples are, the really important colophons are those that read like a title page. The colophon in Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek, BPL MS 2541 is an example of a particularly rich source of information about how the manuscript came to be. The colophon on the last page states: “Pray for the person who made this book, which was completed in 1484 in the city of Maaseik, where we were taking refuge after our convent had burned down” (Fig. 3). These few lines provide a wealth of information, most importantly when and where the book was made, but even something extra about the life (and suffering) of the scribe, who recently lost her home in a fire.

The Last Page of the Book

The second kind of last page that this post highlights is the actual last page of the book. As you can see in Fig. 3, the end of the last page sometimes coincides with the end of the book, or at least with the original medieval part of it. What also happens, quite frequently, in fact, is that the last text page is followed by one or more medieval flyleaves. These are often the remaining blank leaves of a last quire, which were left in place as an extra layer of protection. Flyleaves could also be added, usually in the form of a bifolium that was fixed in between the last quire and the board, to which half of the bifolium was appended as a pastedown.

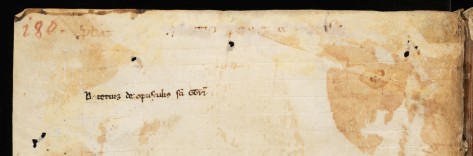

The empty flyleaf – the actual last page of the medieval book – is usually a feast to look at. It was the ideal location to test your pen, to doodle on, or to add informal notes. Some librarians favoured putting the title of the book on the last page, as in Fig. 4, where the librarian wrote “Paterius de opusculis sancta Gregorii” in a book filled with excerpts from works by Gregory the Great.

Far more entertaining (for us) are, of course, the famous doodles that were frequently placed on flyleaves. Testing the pen was a common occurrence, given that the quill had to be cut several times per day. Scribes turned to the last page of a nearby book to jot short sentences of doodle little drawings to see if the nib’s cut was in order. Interestingly, some of these trials seem to combine testing the pen and trying out decorative elements. A good example of this is the page shown in Fig. 5.

While testing his pen, the scribe of these lovely doodles actually produced shapes that would not be out of place on an actual text page as decoration. It is almost as if he was refining a skill while also dealing with the nib of his pen. After all, a nib could be tested with just a few squiggly lines. Thus the last page of the book becomes a test ground for artistic creations: it makes for an attractive last thing to glance at before closing the book.

Note: This was originally posted as my last contribution to the collaborative research blog MedievalFragments. A companion piece on “The First Page of the Medieval Book” can be read here.

I love the doodles ! I’m researching for hand-made book project and your posts are really helping-thank you.

LikeLike