We are surrounded by pieces of scrap paper. We chuck tons of them in the waste bin each year, leave them lying on our desks, use them as bookmarks, stuff them in our pockets, and toss them on the street. And so we usually do not have to look hard or long when we need a piece of paper for our shopping list or for writing down a thought. This was very different in medieval times. Writing material – of any kind – was very expensive back then, which meant that scribes used a paper or parchment sheet to the max: everything was used. As a result, there was nothing obvious lying around on one’s desk that was suitable for scrap material. So how did the medieval person make notes?

In the margin

The most common and sensible location for putting down thoughts, critique or notes was the margin of the medieval book. Consider this: you wouldn’t think so looking at a medieval page, but on average only half of it was filled with the actual text. A shocking fifty to sixty percent was designed to be margin. As inefficient as this may seem, the space came in handy for the reader. As the Middle Ages progressed it became more and more common to resort to the margin for note-taking. Notably, the thirteenth century gave birth to two particularly smart book designs that accommodated such use. Both types are connected to the emerging university, which makes sense as this was a note-taking environment par excellence – then and now.

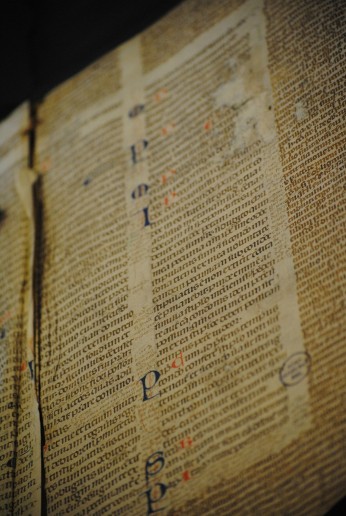

The first of these is seen in Fig. 1, which shows a page of a law manuscript that actually contains two kinds of texts. Found in the two central columns is the Digest of Justianian, written in a slightly larger letter. Draped around it, in a smaller letter, is the commentary to this work: these are the notes of smart teachers from the past, put there collectively to help the reader make sense of the law. This specific style of presenting two works on the one page, where the glosses (commentary) are presented as “square brackets”, is called textus inclusus. An Italian reader in the thirteenth century added his own two-cents to these “prefab” opinions that came with the book: in Fig. 1 we see them scribbled between the two central columns.

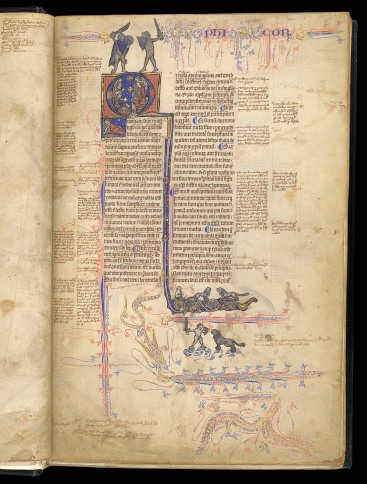

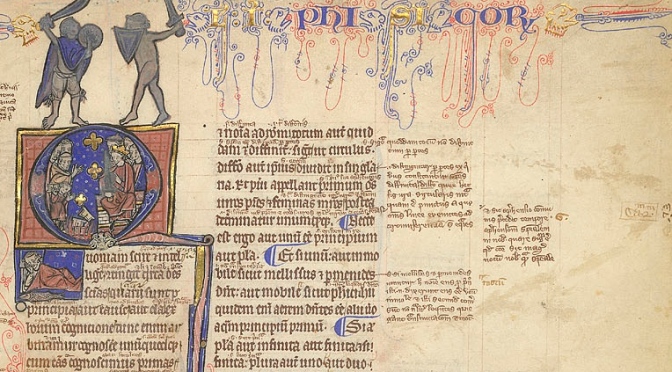

The second thirteenth-century book layout that was specially designed to accommodate note-taking is as clever as the text on its pages. We encounter it first and foremost in manuscripts with works by Aristotle, although the design would spread to other domains, including law and medicine. As seen in Fig. 2, the margins surrounding the Aristotle text (which form the two central columns) were left completely blank by the scribe. The tiny writing that is seen there now is from a student in the Arts Faculty, where the works of Aristotle formed the main textbook, called the Corpus vetustius (the old corpus).

If you look carefully you see five vertical commentary columns marked by thin pencil lines, which allowed for five “pillars” of notes. Cleverly, in this page design the start of the note could be placed at the same height as the Aristotle line on which it commented, not just one time, but five times over! Larger comments were placed in the larger blank areas in the lower margin. Some of these Aristotle textbooks contained up to twenty “zones” for notes, which would ultimately be connected to the main text with the help of symbols resembling our current footnotes.

Yellow sticky notes

As stated, paper and parchment sheets were commonly used to the max, meaning no redundant material was left that could be used for scraps. However, when the animal skin was turned into parchment sheets such redundant material was left over. In the process the outer rim of the dried skin was removed, because these “offcuts” were deemed unsuitable for writing on. The material was too thick for a regular page and its surface was slippery and translucent, not to mention that most offcuts were too small for normal pages. They consequently ended up in the recycling bin of the parchment maker.

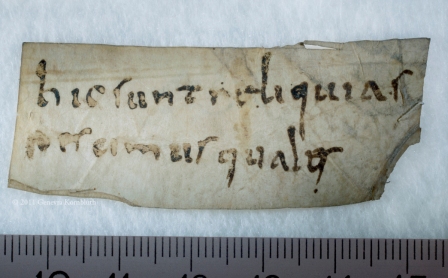

Interestingly, these small, scrappy slips of parchment were sometimes sold to clients. Offcuts were used for text with a short lifespan, such as letters and drafts. In addition, it was used when a text was “utilitarian” and did not need to be produced from regular – more expensive – parchment. An example is seen in Fig. 3, which shows a short description strapped to a bone that belonged to a saint. Such “relic labels” were important because of course nobody wanted to mistake the big toe of St Peter for that of St Paul. Such information was scribbled on the parchment strip, usually in low-quality (fast) handwriting.

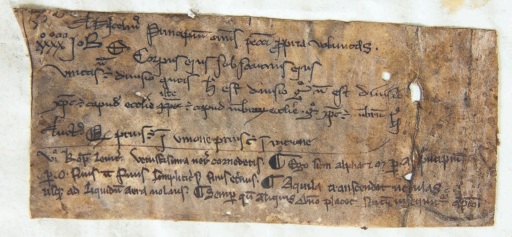

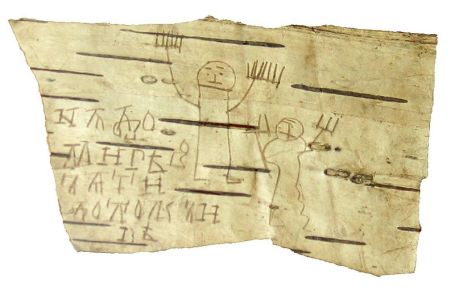

Offcuts were also frequently used by students and scholars, for example for taking notes in the classroom (Fig. 4, more here). In fact, in De discipline scholarum, a guidebook made in the 1230s for students and teachers at the University of Paris, it is explained how a student should bring such slips of parchment to class for taking notes. Interestingly, some of these slips have survived because they were pasted in a student’s textbook, like the one seen in Fig. 4. These are truly the medieval equivalent of our “yellow sticky notes”. The practice of bringing scrap material into the classroom was a much broader medieval phenomenon, as is shown by the famous birch bark notes that survive from 13th-century Russia. Fig. 5 shows funny “stick figure” doodles drawn by the student Onfim as he was sitting, bored no doubt, in class.

The last word: notepad

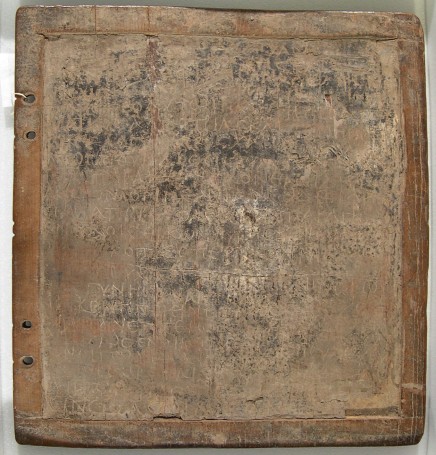

There is evidence that multiple parchment offcuts were sometimes bound together, by pricking a hole in them and pulling a cord through. These bundles, which essentially form a true notepad in the modern sense of the word, could be of considerable size. A specimen in the Universitätsbibliothek Würzburg consists of thirty slips. A type of notepad that was even more popular in medieval times was the wax tablet (here is a collection of them). These, too, were often tied together into a bundle, forming a notepad of perhaps six or so “pages” (Fig. 6, note the holes for the cords on the left side). Smart pages, that is, because the contents could be erased from the soft wax (with the flat back of the stylus), presenting vacant space for fresh thoughts.

great post that really came in handy for my present research. Found confirmation that parchment scraps can be used for ‘utilitarian’ purposes….and do not need perfect writing on them. Only minor nitpicker’s thingy would be that ‘corpus vetustius’ would actually translate als ‘the older book (not ‘the old’ book)…

LikeLike

The picture in Figure 5 made me laugh out loud.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment. I must admit I don’t know as much about the Hebrew tradition as I should – as your useful comment underscores.

LikeLike

In your discussion of note margins, the medieval Talmud (Jewish commentary on the Torah) was written in a unique manner, and was already being written and later printed with a formalized layout of the quote in the center, and formally written notes by various rabbis written around it I very much enjoy your articles. Thank you, Vicki Stone

LikeLike

early inspiration for “Post its!”

LikeLike