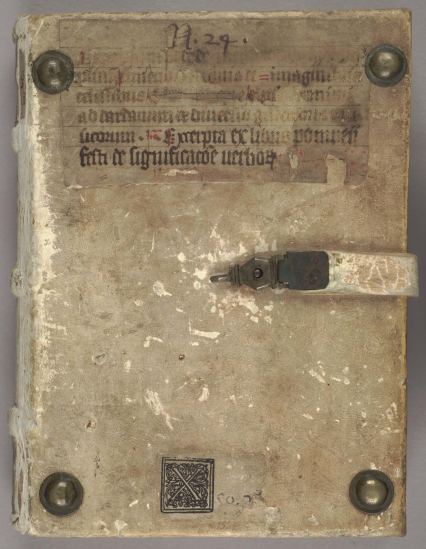

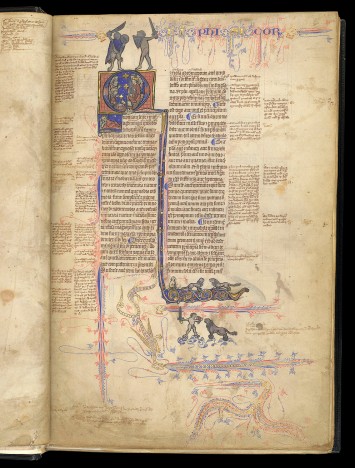

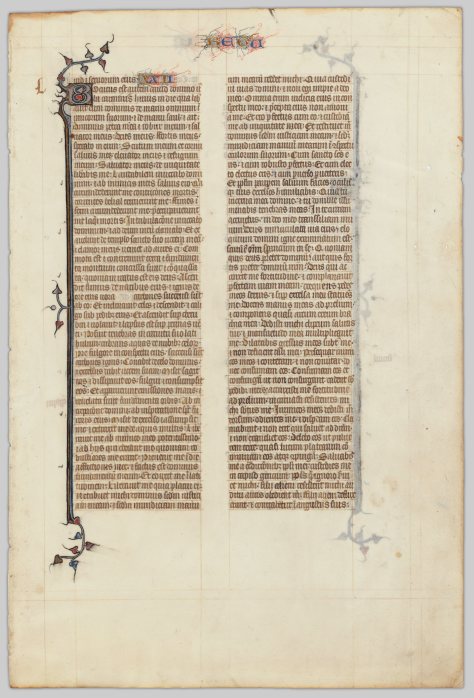

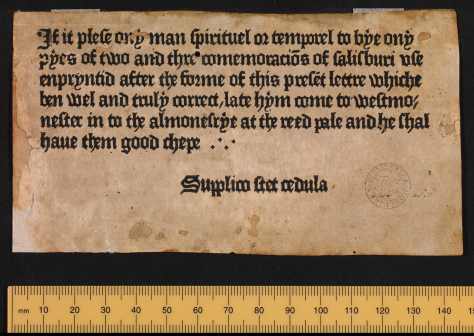

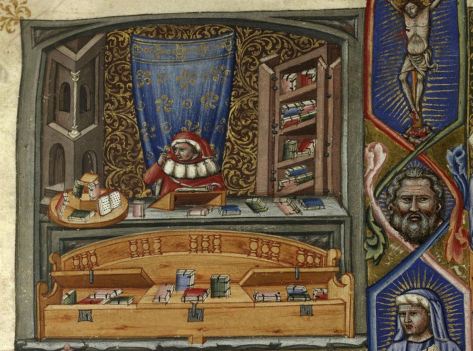

It reads like a horror story. In 1964, the New York rare book dealer Philip Duschnes (d. 1970) bought and subsequently broke a splendid medieval Bible produced in early-fourteenth-century Paris (Figure 1). Every page is adorned with exuberant decoration, usually with gold leaf. The manuscript also contains numerous historiated initials, like the letter S above. With so much beauty on each page, to Duschnes the manuscript must have seemed ideal for breaking and selling by the leaf. In 1965, he began offering individual leaves for sale in his catalogue 169, stating that others from the same manuscript were available. Cut to order.

Duschnes had done the same with other manuscripts, such as the Beauvais Missal (read the full story here; watch this lecture by Lisa Fagin Davis). In 1942 he sold the half-gutted missal to Otto Ege (d. 1951), another infamous manuscript cutter, who added the remains to his “Fifty Original Manuscript Leaves” portfolios, which he put together and sold in the 1940s (more in Gwara 2013 and here). The business of selling freshly-cut leaves from medieval manuscripts proved incredibly lucrative. Today, leaves can be purchased from a variety of sources, including Ebay. This post introduces a newly identified leaf of Duschnes’s bible at the University of British Columbia and it explores what can be known about the original manuscript to which it belonged.

Breaking a book

Duschnes bought his bible at the Sotheby’s auction of 6 July 1964 for £1,500 (approximately $12,000 today). At the time of purchase, the manuscript contained two flyleaves taken from a register from St Albans Abbey, which suggests a St Albans provenance. The abbey’s chronicle, moreover, detailed that abbot Michael de Mentmore (1335-1349) gifted two beautiful bibles to the community (“duas bonas biblias, quarum unam dedit Conventus, alteram suo studio assignavit,” cf. De Hamel 1981, p. 12). Duschnes’s bible was believed to have been one of these two books. Following this assumption, auction catalogues have come to refer to the broken parent manuscript acquired by Duschnes as the “St Albans Bible,” despite the uncertainty surrounding its earliest provenance.

As a result of Duschnes’s dark deed, leaves from “the” St Albans Bible flooded the market and often found new homes in private collections (very few are held in university libraries). Even today, the book’s eye-catching leaves are frequently auctioned at Sotheby’s (2015, 2016), Christie’s (2015, 2019), Bonham’s (2012), and Dreweatts (2017). Auction houses do not usually identify new owners and, while leaves purchased by libraries may in time appear on the radar, especially when they are digitized, those in private collections may not be seen for many decades. The practice of breaking rare books extends to incunabula. This 1928 edition, which appeared in 100 copies, contains no less than 60 original leaves from early printed books; and this one, published in 1964 in 40 copies, holds an original leaf from the 1486 printing of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Even modern rare books are at times cut up. Duschnes dismembered a copy of the famous Kelmscott Chaucer and sold it by the leaf in this 1941 publication.

Leaf in a box

Although the St Albans Bible is rather well-known, I had never seen any of its leaves myself. That changed during a recent visit to The University of British Columbia’s Rare Books and Special Collections. In preparation for my manuscript course at the iSchool, I had a box pulled that was described as “Fragments of medieval manuscripts”. Leafing through the box’s contents, I encountered several attractive, colourful leaves. They all had a sharp inner edge, indicating they were carefully cut out of existing manuscripts. Two fragments in the box were from a liturgical manuscript, one from a breviary, and three from bibles. Unfortunately, there is no documentation available regarding the previous ownership of these fragments.

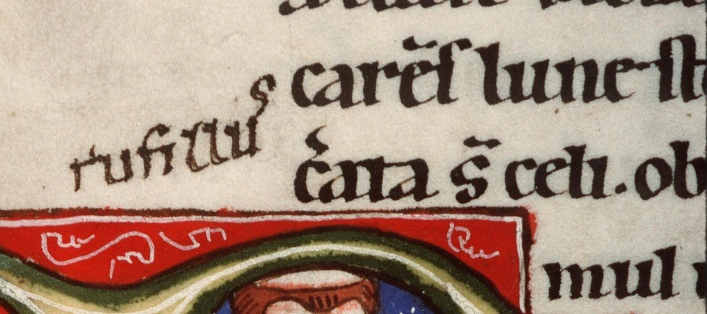

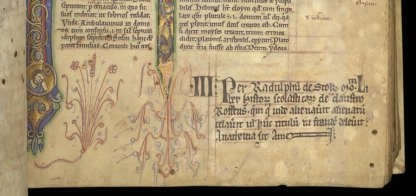

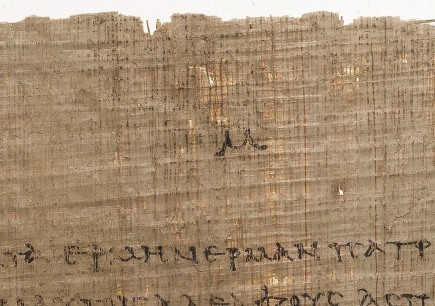

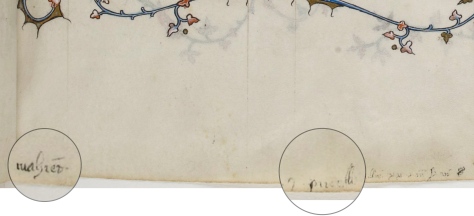

My eye was drawn to one of the bible fragments, because it was older than the others (Fig. 2). A modern pencilled note (now removed) identified it as “The Book of Samuel”. It measured 297×199 mm, was copied in two columns with 46 lines to the column, and judging from the script it appeared to have been made in the early fourteenth century. The other thing that made the leaf stand out was its decoration, which was of very high quality and of French origins. What especially jumped off the page was the elaborate penwork flourishing at the running title (Fig. 3), which is quite unusual. The original manuscript was evidently made by professional artisans, likely in France and presumably in Paris. But who could these individuals be?

The origins of the St Albans Bible

A thorough study of the St Albans Bible has yet to be conducted. This is likely due to the fact that the book was cut into pieces and scattered across multiple institutions and private owners. In parallel to other Parisian products of this age, there are probably three artists at work in the manuscript. One executed the historiated initials, a second the illumination (border decoration, chapter numbers, both made with gold leaf), while a third did the penwork flourishing. A forth individual copied the text. The individuals involved in its production were affiliated to the famous Parisian illuminator and libraire (bookseller) Jean Pucelle. The first to point this out was Christopher de Hamel, who stated that the historiated initials were “in the style of the Parisian illuminator Jean Pucelle” (De Hamel 1981, p. 12).

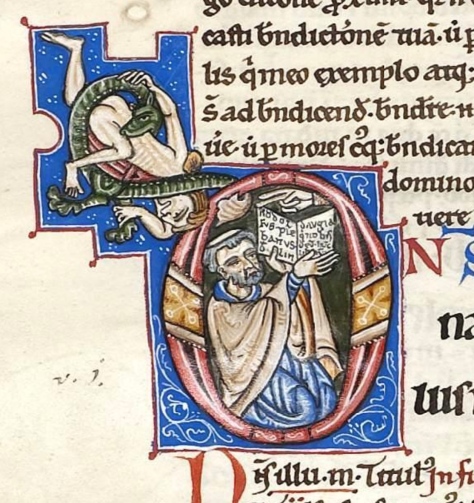

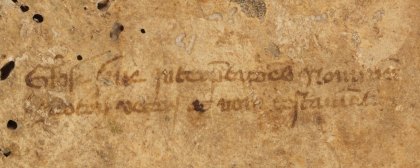

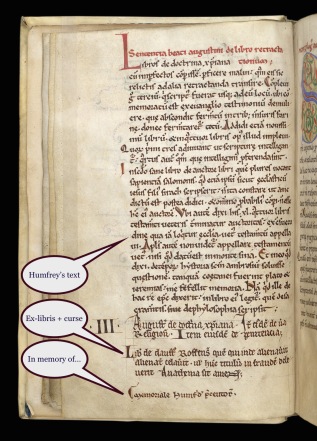

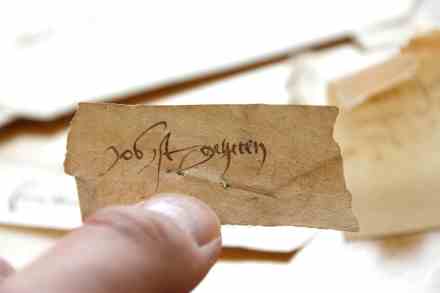

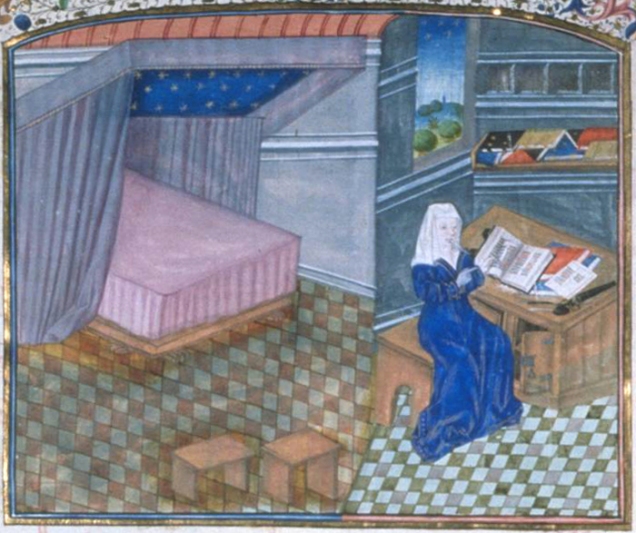

In recent years more information has come to light about the illumination in the St Albans Bible. Mie Kuroiwa attributed the illumination to the Saint Louis Master, a known associate of Pucelle (Kuroiwa 2013, p. 129, no. 35). According to Francois Avril, the Saint Louis Master is the same person as an artist known as “Mahiet” (Keane 2013, p. 133, esp. note 15). Mahiet’s name is written in the famous Belleville Breviary, one of three manuscripts known to have been illuminated by Pucelle (Paris, BnF, latin 10484, digitized here). At fol. 33r Pucelle, who probably supervised the manuscript’s production, wrote down a kind of invoice “Mahiet – J. Pucelle a baillie XX et IIIs – VId,” indicating he needed to pay 23 shilling and 6 denier to the decorator Mahiet (Fig. 4). Other folia mention payments from Pucelle to the illuminator Ancelet, who is probably Anseau de Sens (fol. 62r), and to J. Chevrier (fols. 268r and 300r) (all of these cases were first discussed in Delisle 1884, p. 284).

Teamwork

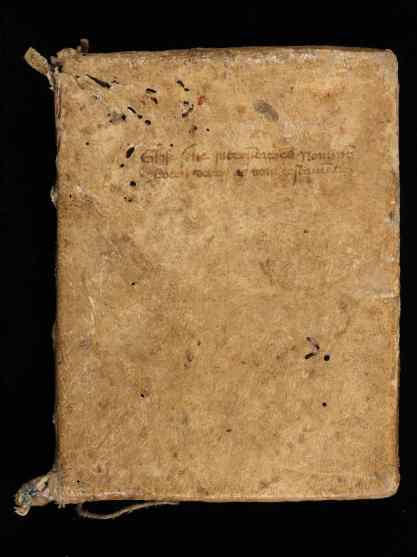

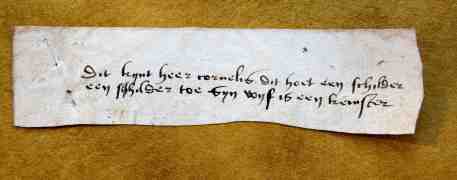

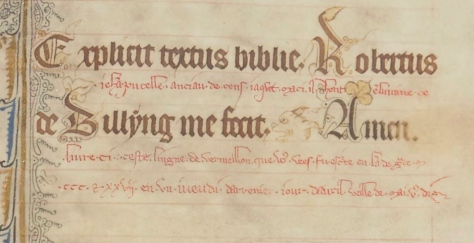

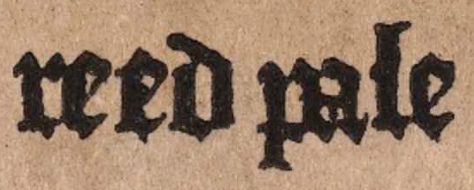

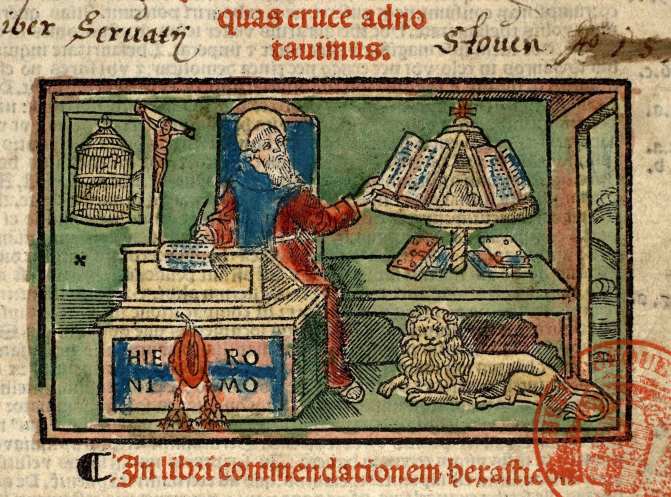

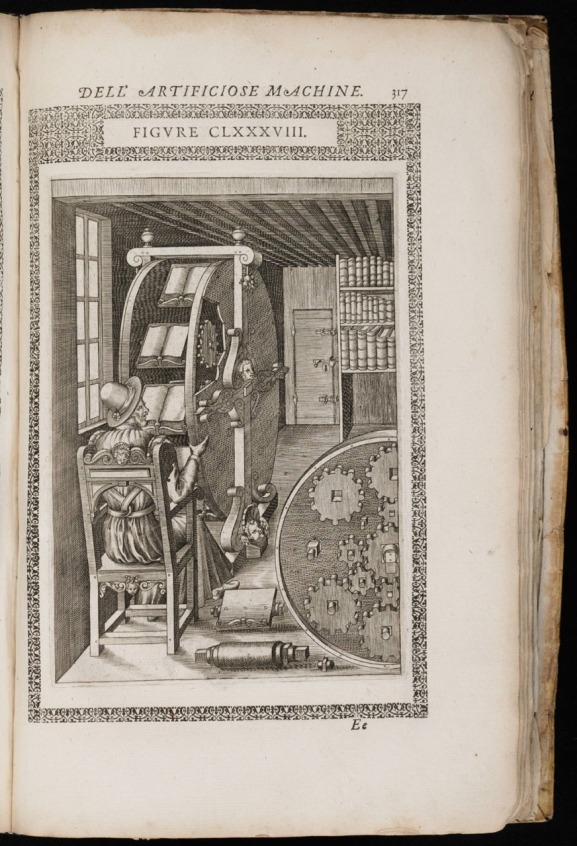

The networks brought together by libraire Pucelle consisted of different artisans each time, although research shows that booksellers preferred to work with the same group of colleagues (for libraires and their teams, see Rouse and Rouse 2000). Another combination of artisans is encountered in the Bible of Robert of Billyng (Paris, BnF, Latin 11935, digitized here). The team introduces itself in the colophon at fol. 642r (Fig. 5). Written in brown ink, the text first states: “Here ends the text of the bible. Robert of Billyng made me. Amen”. Another individual, perhaps Pucelle himself, adds in smaller red script: “Jean Pucelle, Anseau de Sens and Jacques Maci illuminated this book. This vermilion line that you see was written in the year of our Lord 1327, on a Thursday, the last day of April on the eve of May – this I tell you.” (Translation Patrick Moran, UBC; transcription of the colophon in Colophons de manuscrits occidentaux, Vol. 5 (1979), p. 244, nr. 16674.) While it is unclear which decorator did precisely what, again we see Pucelle collaborating with the illuminator Anseau de Sens.

The St Albans Bible was the product of a closely-knit community of artisans at the heart of the Parisian book trade. Those involved in the book’s creation lived and worked in the same street, which made it easy to get teams together (Rouse and Rouse 2000). Pucelle and Jacques Maci, who both worked on the Bible of Robert of Billys, were even neighbours (Rouse and Rouse 2010, Vol. 2, p. 57). Four artisans were brought together to produce the St Albans Bible, although only one of these has been identified by name: the illuminator Mahiet, who had also worked on the Belleville Breviary, the best-known product to come out of the business of Pucelle the libraire. It remains to be determined who produced the historiated initials and the penwork flourishing. The scribe also has to be identified. Behind this team stood, somewhat invisible, a fifth person: the libraire, who had the manuscript produced for a client and who subcontracted the various tasks to artisans in his network (see for this process Kwakkel 2011). Whether this person was Jean Pucelle is not clear. There were plenty of other booksellers around in the Paris book trade, and Mahiet did not exclusively work for Pucelle. While the St Albans Bible can be placed in an important center of book production, in many respects its history remains as incomplete as the book itself.

Post scriptum: In between writing and publishing this post, UBC’s Rare Books and Special Collections purchased a second leaf from the St Albans Bible, which has been digitized together with the leaf that sparked this post (here are direct links to recto and verso). I wish to thank Jan Van Acker (Abdijmuseum Ten Duinen) for correcting my interpretation of the quoted payment to Mahiet by Pucelle.

References and useful sources

Colophons de manuscrits occidentaux des origines au XVIe siècle. 6 vols. Fribourg: Éditions universitaires, 1965-1982).

Delisle, Léopold. “Les livres d’Heures du duc de Berry.” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 29 (1884): 97–110, 281–292, and 391–405.

Delisle, Léopold. La Bible de Robert de Billyng et de Jean Pucelle. Paris: H. Champion, 1910.

Deuchler, Florens. “Jean Pucelle: Facts and Fictions.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 29 (1971): 253-256 (download it here).

Gwara, Scott. Otto Ege’s Manuscripts: A Study of Ege’s Manuscript Collections, Portfolios, and Retail Trade, with a Comprehensive Handlist of Manuscripts Collected or Sold. Cayce, SC: De Brailes, 2013.

de Hamel, Christopher. “Leaf of a Bible Manuscript.” In Fine Books and Book Collecting, edited by Christopher de Hamel and Richard A. Linenthal, 10-12. Leamington Spa: James Hall, 1981.

Keane, Marguerite A. “Collaboration in the Hours of Jeanne de Navarra.” In Jean Pucelle: Innovation and Collaboration in Manuscript Painting, edited by Kyunghee Pyon and Anna D. Russakoff, 131-148. Turnhout: Brepols, 2013.

Kidd, Peter. The McCarthy Collection: French Miniatures (London: Ad Ilissum, 2020, forthcoming).

Kuroiwa, Mie. “Working with Jean Pucelle and His Successors: The Case of the Saint Louis Master (Mahiet?).” In Jean Pucelle: Innovation and Collaboration in Manuscript Painting, edited by Kyunghee Pyon and Anna D. Russakoff, 111-129. Turnhout: Brepols, 2013.

Kwakkel, Erik. “Commercial Organisation and Economic Innovation.” In The Production of Books in England, 1350-1530, edited by Alexandra Gillespie and Daniel Wakelin, 173-191. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Rouse, Richard H., and Mary A. Rouse. Manuscripts and Their Makers: Commercial Book Producers in Medieval Paris, 1200–1500. 2 vols. Studies in Medieval and Early Renaissance Art History 25. Turnhout: Harvey Miller, 2000.

Addendum: known St Albans Bible leaves (institutional libraries only)

I aim to create a student project about this bible based on the surviving leaves. Please contact me at erik.kwakkel [at] ubc.ca if you know where other specimens are kept. The list below includes items with a stable location and is therefore limited to institutional libraries. There are many leaves in private ownership (this publication by Peter Kidd, for example, identifies twenty specimens), but it is hard to trace them and to keep track of their current location (they are more likely to change ownership than those kept in library).

Cambridge, MA, Houghton Library, MS Lat. 471: 1 Samuel, 1 leaf (catalogue entry here).

Dallas, Southern Methodist University, Bridwell Library, MS 64 (low-res image here).

Mānoa, University of Hawaii, Hamilton Library [shelfmark not known to me]: Jeremiah, Job, Matthew, 3 leaves total. Alert by Scott Gwara, USC.

New Haven, Beinecke Library,

Takamiya 87: Ecclesiasticus, 1 leaf (digitized here).

M712.141: 2 Corinthians, 1 leaf (catalogue record here).

Poughkeepsie, Vassar College Archives & Special Collections Library, Scheetz MS 27: Interpretation of Hebrew Names. Alert by Ronald Patkus, head of Special Collections.

Reading, University of Reading Library, MS 90: 1 Chronicles (part image here).

Stanford, Stanford University Library, M1768: Interpretation of Hebrew Names, 1 leaf (digitized here).

St Albans, The Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Alban, Inv. nos. 17.0 and 17.1: Esdras/Nehemiah, 1 leaf; Philippians/Colossians, 1 leaf, with drolleries. Alert by archives team, St Alban Cathedral. More about these two leaves, as well as digital images, in this blog post.

St John’s, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Queen Elizabeth II Library, BS1274 .L3 1325: Deuteronomy, 1 leaf (catalogue entry here, one side digitized here). Alert by Pat Warner, Special Collections Librarian.

Toronto, University of Toronto, Massey College, Gurney Pam 0004: Jeremiah, 1 leaf (catalogue entry here, digitized here).

Tokyo, Museum of Western Art: Psalms, 2 leaves (low-res images here). Alert by Peter Kidd

Vancouver, University of British Columbia Library, Z114 M424: Genesis, 2 Samuel, 2 leaves total (digitized here).

Selfies are by no means an exclusively modern phenomenon. As shown in a previous post on

Selfies are by no means an exclusively modern phenomenon. As shown in a previous post on