By Erik Kwakkel and Giulio Menna (@SexyCodicology)

While this and other blogs introduce you to particular aspects of medieval book production, there are few places on the web that provide a full overview of how handwritten books – or “manuscripts” – were made, especially for those new to the topic. To fill this gap, we (Erik and Giulio) have produced a website called Quill: Books Before Print, through generous support of various institutions (below). The site is now live and available for free to anyone who wants to know more about the handwritten book in the medieval period.

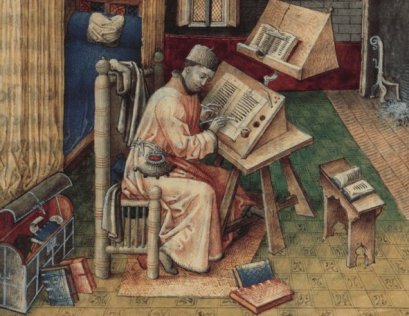

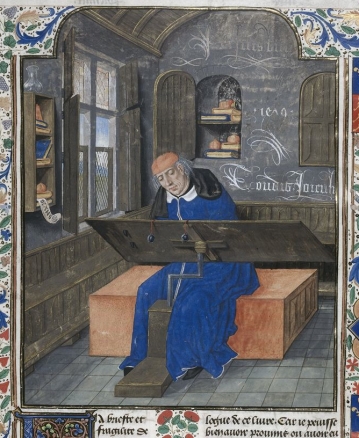

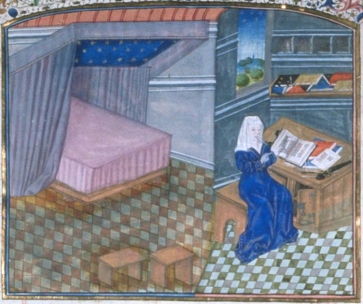

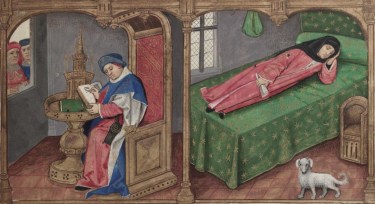

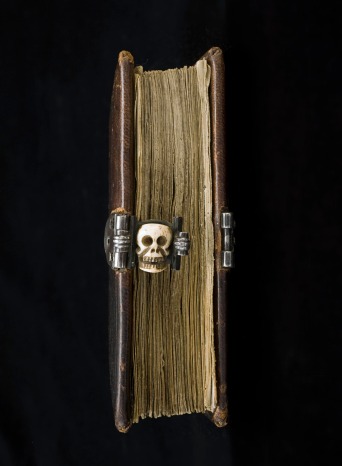

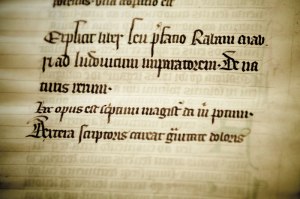

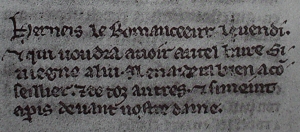

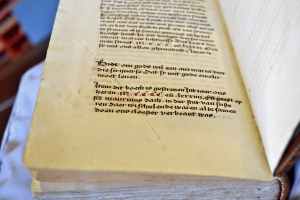

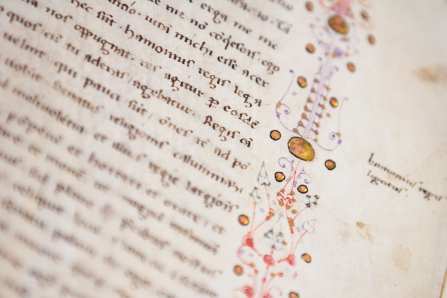

Navigating through Quill shows you what made the manuscript “tick”, and how it ticks. Each of the fifty-odd segments contains an artistic photograph (made by Giulio, who is a professional photographer) and some 150 words of light reading (written by Erik, who is a professional book historian). This post introduces our work, explains how and why we made it, and what we like best about it.

Writing about manuscripts (by Erik Kwakkel)

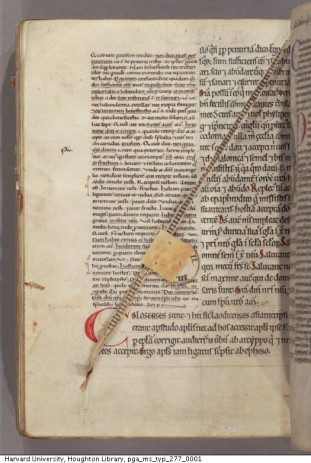

I love writing about manuscripts. Not only do I do so frequently in academic publications (find a list here), but also for an audience beyond the university, for example through social media (this blog, Tumblr) and magazines (I have a regular column in Quest Historie). Writing for non-specialists is fun in that you can just tell a story. However, it also requires a certain approach and tone. The texts I wrote for Quill are first and foremost meant to be entertaining – learning something is a close second. The entries are therefore written in a “light” tone and use “speaking” comparisons. Thus I discuss fragments hidden in bindings as “stowaway“, bookmarks become the “fossilized taste” of medieval readers, and parchment sheets are seen as “dead cows“.

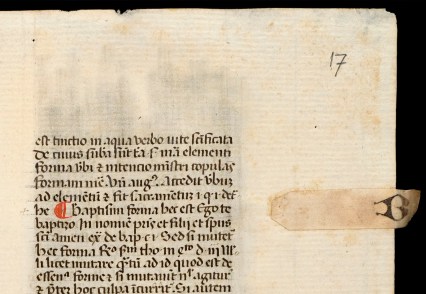

To get this tone right, images are crucial. To write an inspired post about a manuscript, an image needs to “grab” me. Moreover, the trick (both for Quill and my blog posts) is to find a single guiding principle that can carry the text. My blog post on Medieval Selfies is a good example of this, but the same is seen in the entries for Quill. Each of the clickable segments are built around a single observation or angle, which is usually reflected in the title: “Add-on” for the segment on marginal glosses, “One, two, three” for page numbers, and “Mind the gap!” for blank spots on the page.

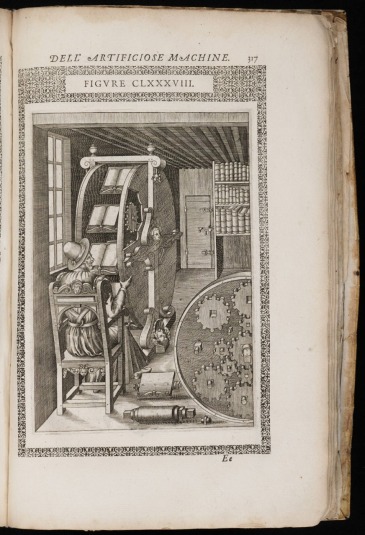

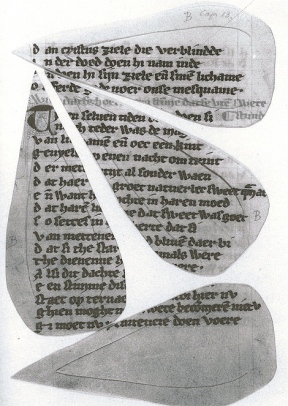

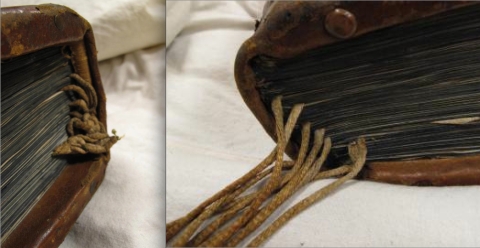

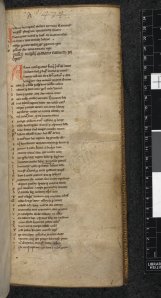

My favourite sections to write are those related to medieval handwriting – script. It is notoriously difficult to do so in clear terms, even in academic papers, when everybody knows precisely what you are talking about. I liked the challenge of providing clear information about such a complex matter as the development from one manner of handwriting to another. Playing with verbal imagery I discuss early-medieval script under the label “The unifier“, while script it develops into is seen as “The divider“. As far as my favourite images are concerned, I’m attached to all of them. Particularly pretty, however, are those that show things you normally don’t see, like a the palimpsest (scratches-away text, vaguely visible) or the backs of the quires, as in Fig. 3.

Photographing manuscripts (by Giulio Menna)

When I was asked to take pictures of medieval manuscripts for this project I was thrilled; when I was told I would essentially have unlimited access to the manuscripts from the exquisite collection in the Leiden University Library, I was as excited as the proverbial child in the candy store. What an opportunity! But then it dawned on me: How do you take photos of manuscripts? How do I make photos that will interest someone who has never seen a manuscript before?

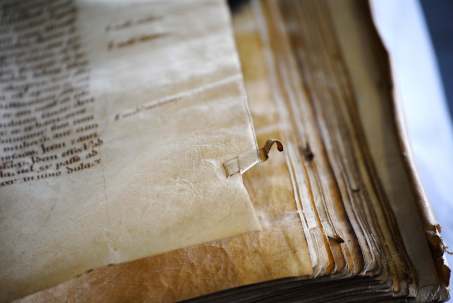

Thanks to Erik’s MA course in manuscript studies I knew exactly what had to be photographed and where to find it in the books. I spent most of the time browsing through manuscript catalogs and manuscripts’ descriptions, searching for the right book to use for the shots. Once the desired detail was found, the actual photography began. First things first: respect the manuscript! I might find a detail that could make a perfect picture, but to get the photo right I would have had to mishandle the manuscript in some way: those pictures did not get taken.

Once an ideal manuscript was found, I used the oldest trick in the book for directing viewer’s attention towards the detail described: depth of field. This would ensure that only the detail in question would be in focus in the picture, and the surroundings would be blurred (Fig. 5 is a good example). I have a very good lens (f/2.8) that allows me to do just that. The lighting was a bit of a problem. Since I was shooting in the Special Collections room I had no direct control over the light. Most of the time I had to wander around the table and find the right angle at which there would be no shadows or reflections.

There are two photos I am particularly fond of. One is the initial P (for Plinius) seen in Fig. 5. It is the opening page of the manuscript, and the letter is welcoming us to the book. I like to believe that this photo captures the moment when you open a manuscript you have never seen before, and you are captivated by unexpected decoration. The initial is very pleasing to the eye: I particularly enjoy the contrast between the old parchment on the right and the white modern paper on the left.

The second image I like very much is of a watermark (Fig. 6). Taking a picture of a watermark was technically challenging: the manuscript’s pages are made of paper, and although paper made in 1600s is more resilient than the contemporary counterpart, it is still delicate and has to be handled with extra care. I had no control over light sources, but I knew that in order to show the watermark I needed a strong light from the back of a page. The plan then became to wait for the sun to go down in the late afternoon, and let some of the light shine through the Special Collections’ windows onto the manuscript. All I had to do then was kneel before the book and take the picture of the naturally bending page.

The last word: enjoy

We hope you will enjoy browsing our website – which was two years in the making – and learn from it at the same time. The site is designed to work optimally with tablets: it’s a true pleasure to swipe the image carousel at the top. We think it provides a sound introduction to making books before print and we hope that the website will be picked up by the broadest possible audience, including instructors at schools and universities. Enjoy!

Credits – Quill: Books Before Print was produced through a grant of De Jonge Akademie (The Young Academy), an offshoot of the Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences, and with logistical support of Leiden University Centre for the Arts in Society (LUCAS). The website would not have been possible without the invaluable support of Leiden University Library and its Special Collections department.