Written by hand, medieval manuscripts are very different from printed books, which started to appear after Gutenberg’s mid-fifteenth-century invention of moving type. One difference in particular is important for our understanding of manuscripts. While printed books were produced in batches of a thousand or more, handwritten copies were made one at the time. In fact, medieval books, especially those made commercially, came to be after a detailed conversation between scribe and reader, a talk that covered all aspects of the manuscript’s production. This is the only way the scribe could ensure the expensive product he was about to make was in sync with what the reader wanted. Consequently, while printed books were shaped generically and according to the printer’s perception of what the (anonymous) “market” preferred, the medieval scribe designed a book according to the explicit instructions of its user.

This principle of one-on-one (of scribe-reader and reader-manuscript) explains why we come across some very strange medieval books. Scribes, especially those that were paid for their work, would accommodate any quirky wish – why on earth not? Here is a selection of five striking manuscripts that are literally outstanding as they are shaped unlike the bulk of surviving medieval manuscripts.

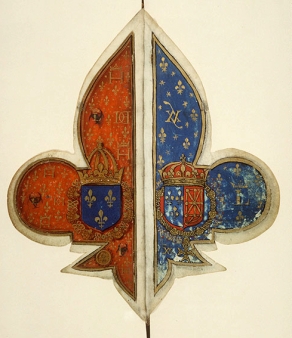

1. Fleur-de-Lis

This Book of Hours has the most peculiar shape (Fig. 1): its pages resemble lily leaves (the yellow background is a paper sheet used for contrast). Such Fleurs-de-Lis were a symbol for French royalty, which puts this special book in a particular setting right away. In fact, we know it was made for king Henry II of France, who used it for private devotion – the Book of Hours contained prayers and other short texts, which were read at set times during the day. Not only does the very shape of the pages testify to the object’s royal patron, so too does the high quality of the decoration (more images here). The manuscript handles extremely well: it measures only 182×80 mm and has a limited number of pages (129 leaves), which means it is light and easy to hold for a long time. Evidently, even during private devotion Henry II was treated like a king.

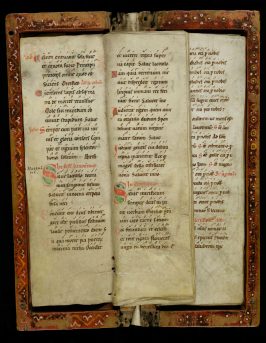

2. Codex Rotundus

This is one of the most peculiar medieval book formats out there (Fig. 2). While you’d expect to see some corners on a page, the Codex Rotundus lacks any at all. Like the previous item, it concerns a Book of Hours, an instrument used for private devotion. Currently kept in the Dombibliothek at Hildesheim as MS 728 (more here), it was originally made in a Bruges workshop for Adolf of Cleves, whose monogram is engraved on the clasps. Adolf was the nephew of Phillip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, which puts this book in a courtly environment, like the previous item. The pages are only 90 mm in diameter, which means this manuscript was designed as a true portable item, perhaps to be brought to church during journeys away from court. The page design came with its own challenges for the binder, however, who had to add no less than three clasps to keep it closed.

3. Heart-Shaped Book

It kind of makes sense to put love poetry in a heart-shaped book (Fig. 3). Still, very few of them survive. Medieval paintings show actual readers prominently showcasing their heart-shaped books, suggesting it must have been a tradition (an example is found here). Copied in the sixteenth century, this particular one from the Danish National Library is the oldest manuscript with love ballads in Danish vernacular (more information here). It contains 83 of them, all composed at the court of King Christian III. The contents may be royal, the appearance of the manuscript certainly is not. In fact, with its scruffy script and mishmash layout, the heart book is far removed from the high-end manuscripts presented so far. Moreover, judging from this added marginal note, the life of the individual who read the book was far removed from the comforts of court: “May God end and turn my misery into a good and happy ending.” He sounds heartbroken.

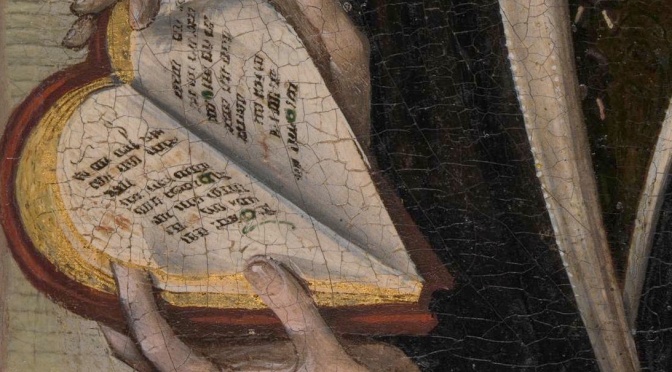

4. Narrow Books

This book is unusual in more than one way. It concerns a hymnal, which was carried through the church during processions (Fig. 4). This is why the book is fitted in a box, which was removed when the pages were used to sing from. What is perhaps more striking about this object is its dimensions: the pages are unusually tall and narrow. Medieval scribes were very strict about the relation between a page’s height and width. It more or less resembles our modern standard in that the width is about 0.7 of the page height (which is 1.0). The narrow format made it possible to hold the book with one hand: the pressure of its weight pressed down on the palm of the hand, not on the finger tips. This tall and high “performance” format was also used in early-modern theatres, and some educators favoured it for use in the classroom, as discussed in a previous blog.

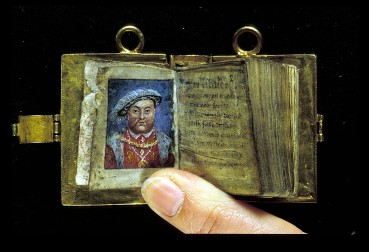

5. Miniature Books

And then there are the miniature books. This tiny object holds an English translation of the Psalms and is only 40 mm in height – less than the short side of your credit card (Fig. 5). It was owned by Anne Boleyn, whose life was cut equally short thanks to her husband Henry VIII, recognisably depicted on the opening page. There are several types of movable books (see this blog “Books on the Go”). As the “loops” on the binding show, this book was designed as a girdle book, which means that it likely dangled from Boleyn’s belt. Although some great specimens survive (see this blog post), such small books were infrequently made in medieval times. This was in part because they could not hold much text and it required particular skills to write such small script. In fact, research shows that less than 1% of surviving manuscripts measure less than 150 mm in height.

While these five examples showcase the exceptional in medieval manuscript culture, one ought to keep in mind that the items stand out because the majority of medieval books do not look like this. On an average day (week, month, year) the book historian will not encounter books like the ones seen here. This is important as it underscores just how strictly medieval scribes adhered to very particular – and the same – rules of book production. Remarkably, these rules of book production were not written down but passed on during training, whether in a monastic environment of in the guild system of the late-medieval cities. While the users of the books above may have been keen to own objects that looked different from the pack, their makers knew this is not what a book was supposed to look like – but they penned it anyway.

Empezar el día aprendiendo!Siempre se nos ha mostrado la idea de monjes transcribiendo grandes y pesados volúmenes .Interesante demostración de variedad.Gracias por”culturizarnos”.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Progressive Rubber Boots.

LikeLike

This is very kind of you – and encouraging to hear. Thanks checking in and for your comment.

LikeLike

Thanks for a marvelous posting! I really enjoyed reading it, you’re a great author.I will be sure to bookmark your blog

and will eventually come back later in life. I want to encourage you to continue your

great job, have a nice afternoon!

LikeLike

very creative for the time since books were very expensive to own and were usually commissioned by the wealthy and were hand printed by monks in monastery’s

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Karadin.

LikeLike