A word of warning: this post may make you want to weep. Last week I blogged about tiny pieces of parchment, paper birch bark, and wood that were filled with short messages from individuals in Antiquity and the Middle Ages (check out Texting in Medieval Times). The snippets – from a soldier’s request for more beer to a duke’s shopping list – were made cheaply and with little care because the messages on them were not meant to be kept long. Although such ephemeral material doesn’t normally survive, it forms an important historical source: it provides a rare glimpse on everyday life in medieval times.

More than in any other medieval document I have seen, such an intimate view of medieval life is provided by a type of written object I encountered for the first time this week (Fig. 1). When visiting the restoration lab at the regional archives in Leiden (Erfgoed Leiden en omstreken) my eyes were drawn to a photograph on the wall that showed a tiny strip of paper from the fifteenth century. I returned the next day to order up the slips from the vault and see for myself what they were all about. Here is the powerful story of a collection of medieval name tags, which may be best consumed with a tissue handy by.

Name tags

The fifteenth-century strips are written in Middle Dutch and kept in the archive of the medieval Holy Spirit Orphanage in the city of Leiden (Dutch: Heilige Geest- of Arme Wees- en Kinderhuis). Founded in 1316, the orphanage was connected to the parish of St Peter (more here). The building is still there and is situated less than 100 meters from the massive Church of Hoogland (Hooglandse Kerk), which can be seen towering over the city from miles away. Until the middle of the twentieth century, the charitable organisation was responsible for the care of foundlings and children.

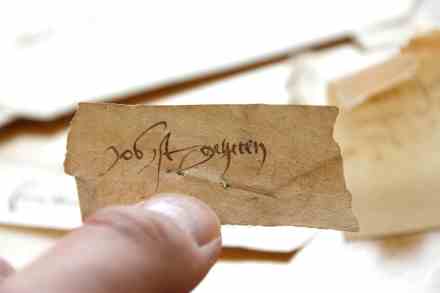

The paper slips, some of which are as small as 10×30 mm, add a real-world dimension to what we know about medieval orphanages. The examples above read: “This child is named Bartholomew” (Fig. 2: Item Dit kint heeit bartelmeis), “Job is his name” (Fig. 3: Job ist geheten), and “This child’s name is William” (Fig. 4: Dit kint hiet Willem). Each slip shows a pair of holes as well as the indent of a pin, which explains what we are looking at: name tags pinned on foundlings’ clothing as they entered the orphanage. As far as I know, this is the only surviving collection of medieval name tags, and it is a mystery why they were kept in the orphanage’s archive for five centuries.

Who wrote them?

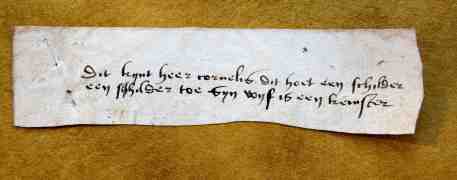

The tag collection can probably be divided into two categories. Some were probably written by one of the masters of the orphanage. The ones seen in Figs. 2-4, for example, are done by an experienced, professional hand. Others, however, are written in a less experienced hand. These may well have been written by the parents. This is supported by the observation that these tags provide more details about the child (Figs. 5-6).

The one seen in Fig. 5 (again with a clear pin mark) reads: “This child is called Cornelius and belongs to a painter whose wife is a wool comber” (Dit kijnt heet cornelis dit hoet een schilder een schilder toe sijn wijf is een kemster). On the tag in Fig. 6 we read “This child is baptised and her name is Mariken” (Dijt kijnt is ghekorstent ende haerren name is mariken). Both show how some children – whether found in the street or dropped off at the orphanage – entered the orphanage with some family history attached, literally.

The only parchment tag provides a particularly detailed history (Fig. 7). It reads “My mother gave me an illegal father, which is why I was brought here as a foundling. Keep this note so that they can pick me up again later. I was baptised and born on St Remigius day.” (Mijn moeder min een onrecht vader gaf daer om ben ic voer een vondelinck gebracht, bewaert dit briefken v[…] opdat nae min weder halen sal ic ben gedopt ende op Remigius dach geboren.) As in the case of Fig. 5-6, it is very likely that the information on this note was provided by the parents, probably as they dropped off their child.

Accompanying booklet

The ten or so surviving slips are kept together with a fifteenth-century booklet, in which they may, in fact, have traveled through time. The title on the first page tells us what we are dealing with: “The Child Book: How the Children Came Here” (Fig. 8: Item dat kijnderbock hoe dat die kijnder hier ghecomen sijen).

The booklet forms the counterpart to the labels, for it registers the orphans and provides information about the location where they were found. We may presume that the foundlings entered the house, often as babies, were tagged, and then processed. However, the entries in the book also contains brief reports from individuals who found foundlings in public spaces and came by to drop them off at the orphanage. The stories on the fifty-odd pages are truly heartbreaking.

On page 33 the following entry is found (Fig. 9). “Item, a child came to us without a name on the Thursday before the feast of St Peter in Chains. And we named it Peter, in the year 1502, for he was found in the Church of Our Lady under a bench.” (Item ons is en kijnt an ghekoemen sonder maem des donnersdacx voer sijnte pieters dach ad vynckula [St Peter in Chains] ende vij hietten pieter int jaer [1502] ende vas gheleit in onsser frouwen kerc onder een banck).

On page 7 a story with unhappy ending is penned down, by two scribes under the heading “anonymous” (sonder naem) (Fig. 10).

The first writes “Item a child was found in the church of St Peter and we named it Luke, on the Sunday before St Luke [= 18 October] in the year 1491. It looked like a newborn child to us, and it had been placed on the altar of St Agnes.” A second hand, in a slightly browner ink, added a short line, sometime later: “Luke died around St Catharine’s day [= 25 November] in the same year.” (Scribe 1: Item een kijnt ende vas ghevonden in sinte pieters kerc ende wij hietent Lucas op die zonnendach voer sinte Lucas anno [1491] ende was een nuo borun kijnt als ons dachten ende lach op sinte aegten altaer. Scribe 2: Lucas starf omtrent sinte katrinen dach actum voerseit.) The second scribe then crossed out the entry in the register.

These narratives form a powerful accompaniment to the paper slips. They report how and where the foundlings were found, and when they came to the orphanage with a paper name tag pinned on their clothes. Handling the paper slips in the archives is a heartbreaking experience: to think that they were made for the sole purpose of providing information about a child whose life was about to change dramatically. The handwriting underscores the emotions that must have been felt by the parents: the text is written in a scruffy manner, often with mistakes in spelling and grammar. For them it must have been a difficult task to write down these mini histories, in more ways than one.

Postscriptum – More on the history of the orphanage in Kees van der Wiel, ‘Dit kint hiet Willem’. De Heilige Geest in Leiden – 700 jaar vondelingen, wezen en jeugdzorg (Leiden: Primavera Pers, 2010), which also features some of the slips. With many thanks to Erfgoed Leiden for letting me photograph the name tags and use them for this post; and to Ed van der Vlist (Royal Library, The Hague) for his help with some readings. Just to emphasise, while I studied and transcribed them, I did not discover the tags, which featured in an exhibition some years ago.