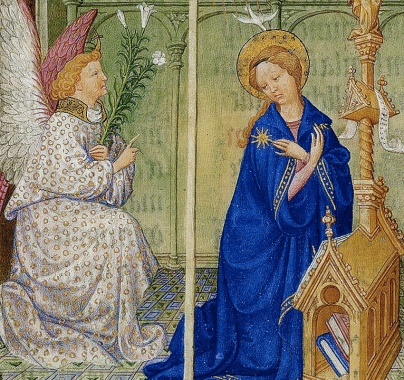

For the book historian Christmas is a great season. It means that a lot of so-called “Annunciation” scenes make their rounds on social media, the biblical story in which the angel Gabriel announces to Mary that she will give birth to God’s son, Christ. There is something very attractive about these scenes for lovers of medieval books. Especially in the later Middle Ages, Mary is shown to be reading when Gabriel breaks the news. The idea was to show her in a holy place engaged in prayer, studies explain (here and here), and to make this connection to the beholder, she was shown with a book.

While this alone tells you a lot about the role of the book in medieval times, the Annunciation scenes have an even more interesting story to tell. They invited medieval decorators to depict a book and a reader engaged with it, life-like and to the best of their abilities. This implies that we get, by proxy, an unusual visual glimpse into the practice of medieval reading: how is the book held, what does the object look like, and what can we tell about its binding? While not every Annunciation scene contains a book, the seasonal images are like spycams intruding into the intimate world of medieval reading.

The tradition

A quick search in public online databases results in hundreds of Annunciation scenes: the British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts returns 160 manuscripts (search here), the French Inititale database no less than 274 (check the result here). This group of 400+ manuscripts provides much information about the tradition of a reading Mary. It is striking, for example, just how many Annunciation scenes depict her with a book. Especially after 1300 there are few without it.

Interestingly, the image databases allow us to gauge in what kind of manuscript the scenes are predominantly found. By far the majority are Book of Hours, but there is also a fair share of Psalters and Bibles, as well as some liturgical books such as Missals. The most popular vehicle of this scene, the Book of Hours, is connected to private devotion, as are many Psalters and some Bibles and Missals. After 1300 private devotion is one of the most common settings for using a book. In other words, the readers of these manuscripts were engaged in precisely the same thing as Mary: praying with a book in their hand.

It is significant that both Mary and the medieval reader are engaging with the book as an object during one of the most important scenes from Christian devotional culture: the birth announcement of Christ. The object had obviously become an important religious tool. What is also striking is that Mary is shown interacting with the book in different ways. She is often caught reading, with the book placed either in her hand or on a table or podium in front of her (Figs. 2-3 and top pic, Angers, BM, 2048). In other cases she is simply holding the object in her hand, either open or closed (Fig. 1). In most cases Mary is depicted in a room or a building with arches (Figs. 1 & 3), providing the illusion of a church or a holy place in general. She is often raising her hands in surprise – although to our modern eyes she seems to gesture “No, thank you!” (Fig. 2).

While it is really easy to find bookish Annunciation scenes from the later medieval period, when the tradition of a reading Mary was well established, examples from before 1100 are rare. The earliest I have been able to find date from the late tenth century. The oldest is the magnificent St Aethelwold Benedictional (Fig. 3), which was made in 963-984 for Aethelwold the Bishop of Winchester (this is a digitised version). Another late-tenth-century example is the so-called Corvey Gospels in Wolfenbüttel, in which Mary is shown with a very thin book in her hand (image here).

Older examples of a reading Mary do exist, but not in books – at least not to such an extent that I was able to easily find them. A scene dating to the ninth century, for example, is found on an ivory situla, a bucket for the holy water used in the Mass (Fig. 4). It shows Mary looking up from her book to see the angel Gabriel making a gesture of blessing with his hand. The arch above her suggests she is in a room, a holy space, as seen in so many manuscript depictions.

Mary had a little book

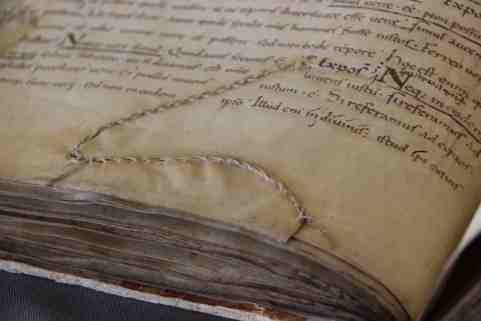

Apart from providing a peek into rooms where readers are interacting with books, these seasonal images also show us what manuscripts in medieval times looked like. Granted, most objects are shown rather generically, but in some cases the decorator shows us realistic details. It is striking, for example, that many images in which Mary is holding her book show her with a surprisingly small object in her hand (Fig. 1). These are likely meant to represent a portable book, a type of manuscript designed to be carried around.

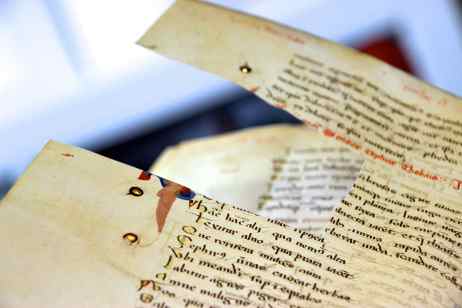

If we expand our scope and include medieval paintings, we are shown more details of the medieval book as a physical object. Notably, the famous Merode Altarpiece from the early fifteenth century shows Mary holding a book fitted in what is called a chemise binding (Fig. 5). This type of binding allowed the reader to fold the book into a piece of cloth or leather extended from the binding. Only a handful survive, so it is a great coincidence that one of them actually covers up an Annunciation scene – albeit that Mary is bookless in this one (Fig. 6).

Curiously, Fig. 5 shows a second book on the table, with a green bag underneath it. This bag is another medieval artifact that survives in very small numbers: the book pouch, which was also used for carrying a book around. The same velvet pouch is seen in the Annunciation scene by Gerard David (c. 1500) – see it here. Both bookbindings in the Merode Altarpiece indicate that the manuscripts Mary is using are portable. More importantly, the beholder would have recognised them as such. By the later Middle Ages, devotional practices had become a “movable feast” and so books used to that end needed to be shown as ambulant. In that sense too the manuscripts depicted here are very realistic.

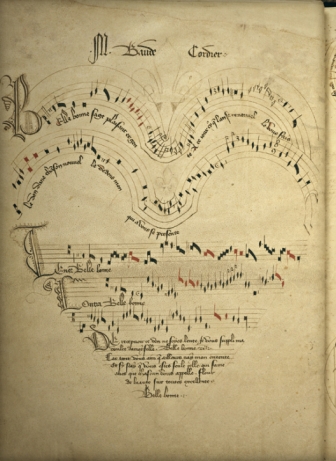

It is interesting that the Merode Altarpiece shows Mary with two books. It appears that this increase started in the fifteenth century and continued into the age of print. The famous “Belles Heures” of Duc du Berry, produced by the Limbourg Brothers in the early fifteenth century, shows Mary in the vicinity of three books as well as a scroll (Fig. 7). In a sixteenth-century woodcut by the famous Albrecht Dürer there are also three books present (here). Both examples give the traditional church environment the feeling of a modest library. Considering that she would soon be with child, to the modern viewer it makes sense that Mary tries to get as much quality time with her books as possible.