At its very heart the medieval book is a vehicle of information. It was an expensive receptacle for text, which was poured onto the page by the scribe, and retrieved by the reader. As strange as this may sound, as a book historian I have limited interest in the actual text found on the medieval page. My job is to look at books, not to read them: knowing author, genre and purpose often suffices for what I do. Very different, however, is my attitude towards words found in the margins, placed there “extra-textually” by scribes and readers. Here we may find information about the production circumstances of a given manuscript and the attitude of scribes or readers towards a text. In most books, there was ample room to add such details, because on average a stunning fifty percent of the medieval page was left blank. It is in this vast emptiness, so often overlooked in editions of texts, that we may pick up key information about the long life of the book.

Pointing a Finger

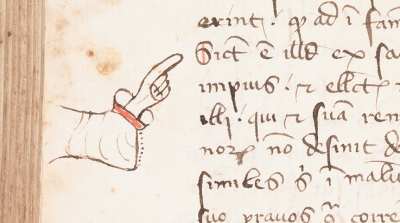

We are taught not to point, but in the margin of the page it is okay. Readers frequently felt the need to mark a certain passage, for example for future reference or to debate its meaning (Fig. 1; more here). To do so, they added manicula (Latin for “little hand”) those highly entertaining pointing fingers. This is good news for us, because they facilitate a look into the mind of a medieval reader. It is not uncommon that a person’s interest shines through the collection of marginal hands in a manuscript. While most individuals simply marked spots with an X, the pointing hand provided a much clearer – and more expressive – signpost. A particularly entertaining pair is found in Berkeley’s Bancroft Library. To mark a particularly long passage we encounter a hand where all five fingers have been drafted into service, while in another case the hand is replaced by an octopus with five tentacles (Fig. 2-3).

From time to time a debatable passage is highlighted by a pointing device that is part of the book’s decoration, like Augustine taking a stance while aiming his spear at a gloss in the text, seen at the top of this post (source).

Critiquing Authorities

There is nothing more inviting to a critical mind than the empty space of the margin. Medieval readers frequently felt the need to vent in that location, for different reasons. Like Augustine and his spear, they would express their dismay about something. There is the Carthusian monk from Herne, for example, who could not handle the poor Latin-Dutch Bible translation he was reading. With a pen shaking from frustration he wrote: “Whoever translated these Gospels, did a very poor job!” (Fig. 4) The same person is encountered in the margins of a different manuscript, where he corrected yet another flawed translation (Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale, MS 2849-51). Providing improved readings in the margins he added the following personal touch: “This is how I would have translated it.” Take that, translator!

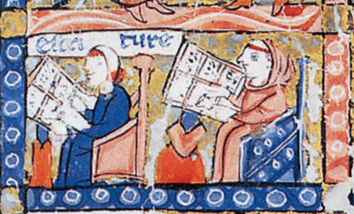

While such explicit remarks are exceptional, critiquing the text in the margin was a normal thing to do as a medieval reader. In most cases he or she would jot down a gloss next to the actual text and connect the two with so-called tie marks – the precursor of our footnote (Fig. 5). This practice became particularly popular in the university classroom of the thirteenth century. The De disciplina scholarum, a student guidebook from Paris, stipulated that wax tablets or tiny slips of parchment were taken into the classroom for note-taking. These notes were later added to the margins of students’ textbooks. Aristotle manuscripts, the main textbook for the Arts Faculty, even provided a clever “zoning” system to accommodate criticism: the margins were broken up into vertical columns where the opinions of master and student would settle (visible in Fig. 5).

Scribes Getting Personal

The examples so far show how marginal additions allow us to peek into the world of those who read manuscripts. Similarly, marginalia bring us closer to those who made the books. Well known are the logistical remarks. From time to time we encounter cross references (“For more on this theme, see this and this page”), remarks about a manuscript’s contents (“Something seems missing here”), or indicators expressing that something is missing (“Vacat”, this is empty). While these statements suggest that book makers put their heart into their scribal work, they can hardly be called “personal”.

That label is appropriate for a rarer type of scribal remark. From the same Charterhouse as the nitty-gritty reader who disliked the Gospel translation comes the following marginal notation: “I put this text here because it also contains work by [the author] Jacob van Maerlant” (Ghent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 1374, fol. 129r). Says the same scribe in another manuscript: “I copied this here because it analyses faith” (Vienna, ÖNB, Cod. 13.708, fol. 218r). With these remarks the scribe appears to deliver a personal message to the reader, sharing his rationale for compiling the collections.

Other personal statements come from the world of commercial book production. Here it was all about making a profit out of producing and selling books (Fig. 6). Some artisans wrote their name and location in the margin, like a medieval form of spam (I wrote about it here). Not every paid scribe was equally happy with what he received and from time to time we encounter complaints. On 15 May 1444, at nine o’clock in the evening, the scribe Henry of Damme finished a copy of a chronicle about the city of Brussels, which he had copied for the municipal government. In a corner of a flyleaf he tallies his expenses: “11 golden letters, 8 shilling each; 700 (initial) letters with double shafts, 7 shilling for each hundred; and 35 quires of text, each 16 leaves, at 3 shilling each” (source, in Dutch). Unsatisfied as he was, he wrote the following underneath the last text line: Pro tali precio nunquam plus scriber volo: “For such a (small) amount I won’t write again!” (Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale, MS 19607, fol. CCLXXVr).

The breakdown of these numbers show that Henry had little reason for complaining: he earned 1.4 shilling a day, which is about the same as his fellow scribes working in the chancery. While the Carthusian scribe who explained the reasons for putting a collection together made a positive and personable connection to the readers of his books, Henry’s remarks, by contrast, expose him as a bit of a greedy whiner.

I love marginalia! My own books are full of them -this post reveals it be a very human reaction-great connection to the past. Thank you for helping me to re-engage my academic brain!

LikeLike

Came here via NY Daily News. What a treasure. =) Will check out the rest of your site.

LikeLike

It’s a great collection – thanks for your interest!

LikeLike

I am fascinated by your discoveries and observations. The Walters Museum here in Baltimore has a terrific manuscript collection and has had some exhibits you would have enjoyed, thank you

LikeLike

Thank you so much!

LikeLike

Absolutely fine, as long as you keep the caption details in place (city, institution, number): that is a copyright-requirement of the libraries.

LikeLike

Hi! I found your blog through the Colossal article. I, too, love medieval manuscripts and am greatly enjoying your posts. I want to mention your work with medieval doodles on my blog and am wondering if I may have permission to use one or two of your images. Thanks!

LikeLike