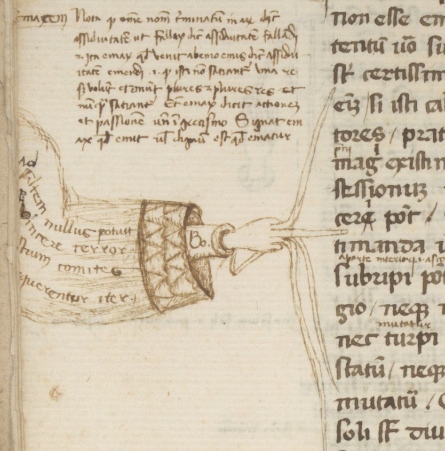

We are taught not to point. Pointing with your finger is rude, even though it is often extremely convenient and efficient. Medieval readers do not seem to have been hindered by this convention: in the margins of books before print one frequently encounters a manicula or “little hand”. While the purpose of these “helping hands” was the same (they were usually put there to highlight an important passage), their appearance varies considerably. This is due to the fact that there was no standard format for the hand – beyond the point that it had to resemble one (Fig. 1).

Since the reader was able to shape hand and finger as he or she saw fit, we can sometimes recognise a particular reader within a single manuscript, or even within the books of a library. The charming hands function as a kind of fingerprint of a particular reader, allowing us to assess what he or she found important about a book or a collection of books. This post celebrates the variety encountered in these personal and permanent pointers, from the plain hand to the exotic octopus.

Plain hands

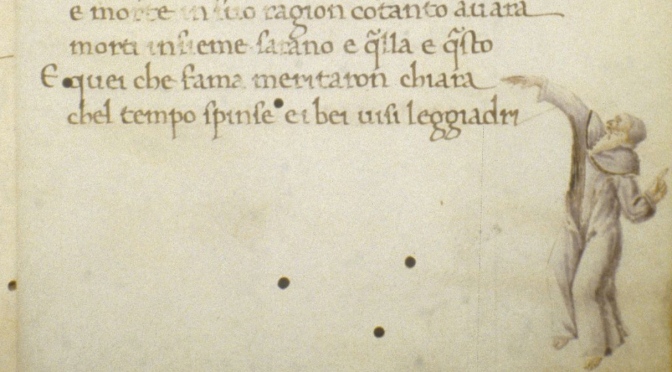

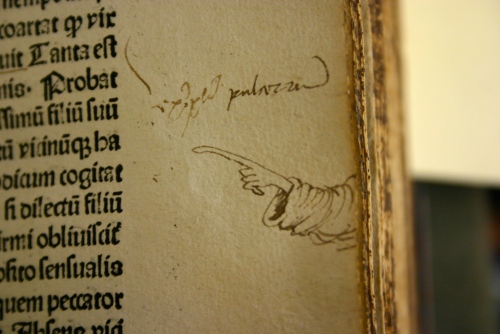

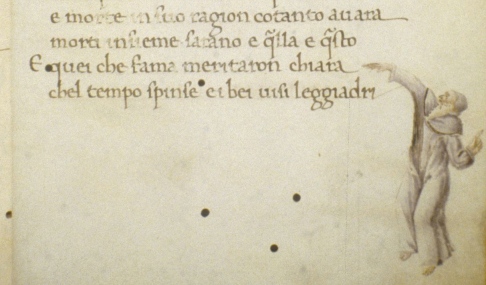

The term “manicula” is somewhat deceptive. Pointing hands are almost never just pointing hands. Usually there are arms attached, which may even be fitted in sleeves. Sometimes these sleeves are elaborate and realistic, with folds and all (Fig. 2). It is an exciting thought that the medieval reader who added this tiny drawing in the margin may simply have looked down and replicated his own arm. If this is true, we may potentially be able to tell something about his status, for example whether he is a monk (wearing a habit) or a private individual. This inference potentially prompts an exciting kind of study, which has never been undertaken. It also makes you wonder what to think of a full figure as seen in Fig. 3. It is tempting to think that we are looking at the reader here – although, realistically, this would probably be pushing it too far.

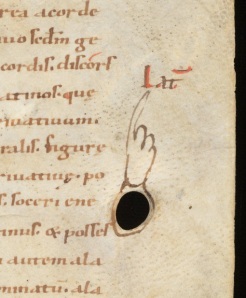

Looking at surviving maniculae in medieval books sparks yet another correction: tiny hands are often not really tiny. The one seen in Fig. 1 takes up much of the marginal space. It is a very natural looking hand, with the digits in just the right shape and angle. There is even a nail attached to the finger – the first I have encountered. As you would expect, pointing fingers are attached to both left and right hands. Without having done any conclusive research on this, it appears right hands are more common than left ones.

Elaborate hands

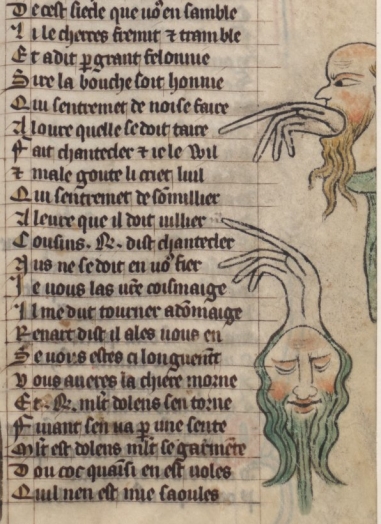

Not all pointing hands look realistic. The one seen in Fig. 2 is representative of a phenomenon that is frequently encountered: the pointing finger is stretched well beyond human proportions. The reason, of course, is that the tip of the finger needs to point out one particular line – otherwise the system would fail. The fingers of a pointing hand can easily be more elaborate. The hand in Fig. 4 is not only unusual in the size of the sleeve and the notes written on it, what really jumps out is the size of the fingers and the way in which they are fanning out. The reader no doubt meant to point out an extensive passage and so more fingers were drafted into service. He did the same thing elsewhere in the manuscript, this time using an octopus with spread-out tentacles (Fig. 5). Another way to point out more than one line is seen in Fig. 6: just use two hands!

Exotic hands

Then there are the really exotic hands, which are turned into a visual feast. Fig. 7 shows and an arm that was turned into the body of a dragon, while the hands in Fig. 8 (which look like ladies’ gloves) are attached to the wrong location on the human body. These hands are not just meant to point out an important passage, they must also have been intended to bring a smile on the reader’s face.

Interestingly, while the dragon could easily have been doodled by the reader himself, the depictions seen in Fig. 8 are carefully designed and painted. These pointing hands – the manuscript contains many of them – were probably done professionally. If this inference is correct, it suggests that the reader asked the artisan to insert them during production. This is interesting because it means that the reader already knew what passages he would wanted to have highlighted. It appears he already knew the text well before he owned a copy.

The range of helping hands is remarkable. There were other, easier ways to mark important passages, such as lines and crosses placed in the margin. However, in some cases readers preferred to have a more pronounced signpost. While a tiny line could be overlooked, the hands – particularly if executed with color – really pulled your attention to the thing that mattered. That particular sentiment lives on in modern times, I recently noticed when stopping at a traffic light for bikers in Leiden, The Netherlands, where I live (Fig. 8). “Dear biker”, the modern (sleeveless) manicula expresses, “push the button if you don’t want to stand here all day.” Now that is helpful.