In the beginning there were animals and they were deemed suitable for writing on. Before paper was introduced in medieval Europe, the book’s origins walked in the meadow as calf, goat, and sheep. Little did they know that their skin would become parchment and filled with poetry, songs, and stern theological lessons. From beast to book: each page in a medieval codex represents an end and a beginning.

We owe a lot to medieval flocks. Jointly, uncountable animals secured the survival of classical and medieval texts in their afterlives, transporting them to the safety of the printing age, and our own bookcases. The manner of transportation varied. Some rides were luxurious and pampered readers with velvety pages; others were third class. Parchment makers sold different grades of sheets, from cheap to expensive, and visual perfection drove up the price. As did size: large books with perfect skin were the SUVs among manuscripts.

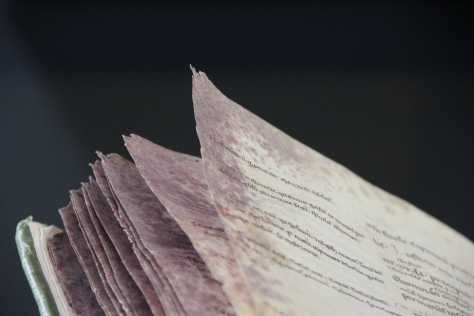

Did medieval readers give any thought to holding a beast for a book? Parchment made with care hid its beginnings well. Properly de-haired, trimmed and sanded, a page was just a page. Except when the knife of the parchment maker slipped and produced a tiny cut, which showed up as an oval hole on the page (as seen here). Because it was harder to clean the area around it, stubborn hair tended to stay in place. It made the animal come out of hiding, put it back into full view: this story of Lucan was evidently copied on the skin of a calf with white hair.

Images: Leiden, University Library, BUR Q 1: Lucan, De bello civili (digitized here, find the page here). Larger photo my own, the other is taken from the digitized object.