Most of us have said “I love this book!” at one point or another. However, what we mean by it may differ a great deal. If you are like me, this statement has little to do with how enjoyable a given read is. Instead, it is literally: what a great object I’m holding! The other day I was in Leiden University Library, my stomping grounds, looking at a ninth-century manuscript containing various school texts. I thumbed through its leaves and saw different individuals writing down different texts. I saw readers mumbling over worn pages, interacting with texts, crossing out lines and writing down notes in the margins. And I saw how even later readers had added their own pages with additions. And that is when I heard myself whisper: “I love this book.” To me, this quirky, millennium-old object, with its dirty and heavily used pages, was simply paradise. But what makes these worn manuscripts so attractive – and useful – for the historian of the medieval book?

Reading the Reader

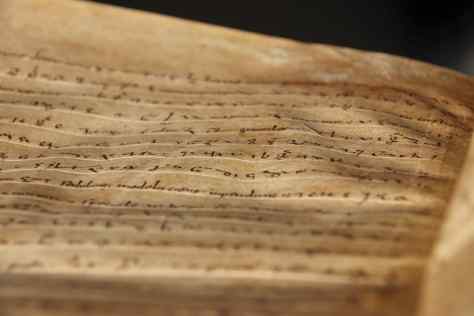

Some medieval books look like they were made yesterday. The pristine page still breaths medieval air, as if its maker has just left the room. It’s not difficult to like this type of manuscript: the excitement when you open it is like entering your brand new car for the first time. Or rather, your brand new vintage car, as most medieval manuscripts are pretty worn. These are used books – and they have often been so for five hundred to a thousand years. Importantly, their wear and tear has a story to tell: medieval users were pragmatic and the traces they left behind tell us a lot about how they used a manuscript.

For example, a reader may sew a tiny piece of string in the corner of the page (Fig. 1). In fact, this particular manuscript contains many of these make-shift bookmarks, as if the reader was sitting behind the book with needle and thread ready at hand. Bookmarks are great little devices, smart even, as this earlier post shows. Interestingly, they are also quite telling about the popularity of a specific book and in particular which pages were most important – since that is why a reader would like quick access to them.

Dirt is another indicator of frequent use and, in a sense, of a book’s popularity. The same manuscript as in Fig. 1 has a lot of dirt build-up in the folds. There are even leaves from trees encountered from time to time (Fig. 2). It is possible that these acted as environmentally-friendly bookmarks, ultimately helping us to gauge a reader’s interest.

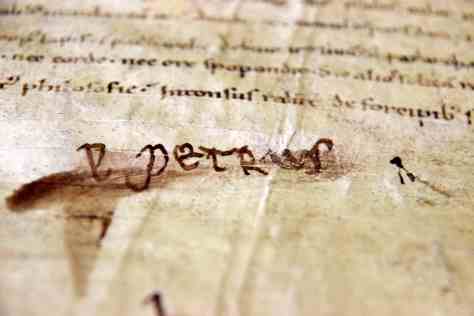

A particularly engaging mark of use are instances where a medieval individual introduces himself to you. “Hello my name is Peter,” the inscription Petrus at the bottom of a twelfth-century page seems to express (Fig. 3). The name, written in a hesitant and uneasy fashion, has the look of having been written by a person learning to write, a child perhaps. Given that this book was produced in a monastic environment, we may well be dealing with a novice (a young member of the community) who had just mastered pen and ink. “I can write,” this inscription says. “I am Peter and I can write!”

Wear and tear is another way in which the manuscript shows that it was used a lot – that it had been popular among a group of medieval readers. It is not uncommon to see pronounced discolouration at the lower left corner of the page. The dark patches that can sometimes be observed there result from generations of fingers turning the page. Pages with such dirty lower corners usually also turn quite easily, as if the structure of the parchment is loosened up by the repeated turning of pages. Occasionally one encounters a page like the one seen in Fig. 4, which is dirty all over its surface. One wonders how clean the readers’ hands were – also after consulting such a dirty book.

Use or abuse?

The previous examples have drawn attention to an interesting truism: the more a manuscript was used, the dirtier it became. It appears, interestingly, that medieval readers had a very different attitude towards how one ought to interact with books. I don’t think many readers today would be willing to stab one of their books and insert a string, as seen in Fig. 1. And who would write his or her name on the page in such joyful, large script as the unknown Peter did in Fig. 4? Judging from the high frequency with which medieval readers jotted down notes in the margins, it becomes clear that books were seen as utilitarian objects, which could be treated in any way the reader saw fit. If the clarity of a text increased from having marginal notes written next to it, then the benefit of having those notes there would override any feelings of hesitation produced by having to write in your book.

However, the line between use and abuse is thin. You had to be careful when writing new text in the margins of an existing book, because while the ink was still wet it could easily produce smudges. The reader who annotated the manuscript with Ovid in Fig. 6, wiped out his thought (phrased in Dutch vernacular) by mistake. Peter-Who-Could-Write in Fig. 3 made the same mistake, because his name is also smudged. Peter’s finger must have been really dirty, because the parchment surrounding his name shows a lot of inky stains.

There are many examples of medieval manuscripts being a victim of their readers’ abuse. Fortunately for us, some abuses provide clues as to how the book was used. A good example of this is the manuscript page seen in Fig. 6, which shows a law manuscript with candle wax dripped all over the text – note the big yellow blob. It is not difficult to see a medieval student at work, late at night, perhaps studying for his exam the next day. It is dark and the only light is artificial: a candle. However, using a candle is risky, especially when you are trying to read a tiny note that is written in the between the lines: drip.

Dirt and other undesired elements on the page are very frequently encountered and the examples here show how they can be evidence of how the reader interacted with the manuscript. From time to time, however, rather than showing negligence or carelessness, human interaction with medieval books shows something else, for example how liberal or prudish a reader was. Check out what the user of the fencing manual in Fig. 7 did to cover up the private parts of the two opponents: big fat drops of red wax (of the type used for making seals) were splashed on the page to bring the scenes in line with the standards of the prudish reader. No problem to behold two stabbing figures in a battle for survival, but we don’t want to see them do it naked. What a dirty book.

Postscriptum: Kate Rudy (St Andrews) has done substantial work on dirt in medieval books and has even found a way to quantify dirt with the help of a densitometer (read about it here).

Erik, Thanks so much for the reply. I do appreciate it – and the news about Szirmai at Scribd.

LikeLike

I did not know anything about flax used for this purpose, but your query prompted me to consult Szirmai, The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding, and he discusses the materials at various locations. At 117, importantly, while discussing Carolingian bindings, he describes a sample research he undertook based on St Gall manuscripts, 9th-12th. Flax is found in 15 samples. More data at p. 190. I would check that out. BTW, his book can be downloaded, legally it appears, throught Scribd.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Erik, a manuscript is described as follows:

“Manuscripts bound between 1300-1600 generally were sewn with linen thread onto raised, double, tawed-leather thongs. This manuscript is sewn with bast fibre onto double cords made of flax, which are raised on the spine of the textblock . Although it is not unheard of for a fifteenth-century manuscript to be sewn onto flax supports, as this manuscript is, it is less usual than the use of leather supports. ”

I’m not sure how to take “not unheard of”. Should I take it to mean a little unusual, really quite unusual, or as ‘nearly unheard of’,

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s great to hear!

LikeLike

I have your blog on my phone screen. It’s fascinating. The writing has joy and passion that make every detail so precious.

LikeLike

A fascinating post! I love old books too and enjoy reading the inscriptions.

LikeLike

That’s great – appreciated!

LikeLike

Thank you very much, I always enjoy your posts. I’ve sent the link to a user group that delights in snail mail, and I’m sure will relish these posts.

LikeLike

It’s recommended that you wash your hands before consulting a manuscript. Gloves can actually be harmful to old books: http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2011/08/white-gloves-or-not-white-gloves.html.

LikeLiked by 2 people

And you are not required to wear latex gloves to protect paper from germs?

LikeLike

The books are kept in (in my case) Leiden University Library, where they are stored in boxes. I consult them like any other book: with my hands.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Looks like the kind dripped from a stick. It’s post-medieval for sure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazing!

LikeLike

Very interesting post and blog! Was just wondering how do you get access to these old manuscripts/books? I would imagine they are kept under glass or filed away in special section of the library, but perhaps I am wrong.

What’s also interesting, is how a very old vandalism (a man/guy/boy writing down his name in the book), can feel like a very interesting and valuable addition to the book itself when looked at by us nowadays.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder what kind of wax the drip was? Beeswax would have been more expensive than tallow for example, as well as smelling quite different as I imagine the reader poring over the text in the dark 🙂

LikeLike

@vickyomand: I once found a calcified bat inside a copy of Corpus Juris Secundum in the Canal Zone law library. How it got there I have no idea.

LikeLike

Thanks for your interest!

LikeLike

Thank you for this blog! Follow avidly on twitter as dieoervlakte.

LikeLike

So interesting about even the very old books containing interesting things, and different marks left there. I’ve always loved finding forgotten items in books.

LikeLike

You are welcome!

LikeLike

Thanks, Erik, for this interesting information. 🙂 — Suzanne

LikeLiked by 1 person

We have the same thing at home, that favourite meals reveal themselves. It’s lovely how books tell all these secret stories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely blog. My husband calls the dirt left on pages, the cookbook effect. You can easily see my favorite recipes in my oldest cookbooks because the book falls open to them, and those pages have a lot of splotches, as well as margin notes. Other than that, I don’t write in books very often.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I work in a used bookstore (for charity) and have found wonderful old books but some smell rotten, full of smoke, have dead insects, and worms. I like to think how many hands a books has passed through, but feel creepy when someone donates forgotten, sometimes mildewed, wonderful old books. Eke.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Chris The Story Reading Ape's Blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How timely – and nice to know you enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Kate McClelland.

LikeLike

Having just read through the proofs of the catalogue for Les Enluminures’ upcoming exhibition, Traces, on the marks and materials bookmakers, readers, and owners left in their manuscripts, I was thrilled to see this post today and to peruse the traces you have shared with us. What a delightful range of dirty books and what a lovely read!

(And if you are interested in checking out the dirty old books in our exhibition, they will be on display in New York in April, and the catalogue will go up on our website in its entirety around the same time.)

LikeLike

The red wax could actually make the book much more lurid than intended.

LikeLiked by 2 people

A time traveller!

LikeLike

*like*

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have always wondered if the fly that fell out of a mediaeval plainsong ms at the Bodleian, was as old as the book or somewhere in between then and 1980!

LikeLike

It is still hard to resist shouting from the review, I loved this book. Loved the article!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree!

LikeLike

Wonderful article. My problem if I were to be let loose with a medieval book might be wanting to answer a long-ago scholar’s observations! I love picking up a book in the library and finding a kindred soul has left notes in the margin- have seen some with running commentaries. Splats and smudges tell me that this book has been read by someone who, like me, cannot stop reading while eating or drinking, or perhaps suffered a paper cut while reading. Often, if I find the temptation to extensively annotate a library book, I buy my own copy, knowing I will need it for the long term anyway, If I can, I’ll buy a used copy, hoping for insightful (or entertaining) notes. Dirty books are the best kind- you know they’ve been read by other people.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant! The worst thing I’ve found in a book, a charity shop book, was a dead earwig… And the best thing was a train ticket from an early copy of A Kind of Loving, I keep it with me at all times, I’m not sure why.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Terrif…heart flipped when you wrote of pristine med’l books as having the magic of new cars…wonderful analogy!

LikeLike