From time to time this blog shows damaged manuscripts. One may be inclined to think that books are better off in pristine condition. However, Karin Scheper, conservator at the University Library Leiden, explains why it is sometimes better to leave a book be. Here is an intriguing guest post about useful disrepair and the upsides of damage. Enjoy! Erik Kwakkel

Custodians and owners of old books will sometimes have to make tough decisions. They want their books to be used – why else would they have them? – yet they also want them to be preserved for the future as well. In the case of manuscripts and early printed books, the materials themselves are old and often fragile, and part of the textblock or binding may have come apart. While in most cases it would technically be possible to repair the damage, this is not always the best option for the book or the user. Instead, a conservation specialist may advise to simply box a book and not treat it at all, or propose minor treatment and consolidation only of the fragile state. Is that a result of sparse conservation budgets, or can there be other reasons?

A conservator evaluates the severity of the damage. Not all deterioration processes are progressive, and some damage may have occurred centuries ago without causing problems. Other conditions, such as deformations or splits in flexing materials may cause severe threats and further loss of material. The book’s current use, its historical value, and its relation to a collection are of course factors of importance when making conservation decisions.

The book as a physical object contains much more information than its contents alone; this blog demonstrates that in every posting. In spite of the fact that an increasing number of manuscripts and old prints are available online, the material object remains valuable – and may even become more valuable. One of the unique values of the physical book is that it contains historical evidence that is not accessible in a digital format. With a damaged object this information may be more easily accessible than in a well-preserved or restored book. The damage itself may reveal historical circumstances or shed light on former use, and in addition, damage may provide access to the interior of the structure. This can teach us what materials were used and what decisions the original bookbinder made, and it may connect the book to a certain region or time frame. Damage can be beneficial for book historians, and repairing damage may deprive them of valuable information. One way to safeguard such evidence is extensive documentation of the object prior to conservation treatment. However, if the condition of the book allows it, minimal intervention is an attractive option that respects the book’s integrity, and sometimes doing nothing may even be the best decision for the moment.

Three cases from the Leiden university collections illustrate such preservation issues and address the question whether the benefit of a conservation treatment outweighs the benefit of not treating a book.

A slotted spine

In the early sixteenth century a novel method of binding books in parchment was developed in Italy. Books with raised bands always seemed to function more naturally in leather than in parchment; the three-dimensional shape of the spine with its raised sewing supports and the stiffness of the parchment were not a winning combination. Italian bookbinders solved the problem by cutting slots in the parchment at the positions of the raised bands, and they use white tawed leather at these positions instead (Fig. 1). This technique was used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and appears to be confined to Italy. (See here for more details about how such bindings were made.)

Both parchment and leather discolour over time, after which it becomes difficult to distinguish between the two materials. In addition, the ‘slotted spine’ as a technique is relatively unknown, and it is usually not easy to discern something one is not familiar with. With this particular technique, the characteristics may become more indistinct when the damaged spine of such a book is treated, and as a result an untrained eye may just be under the impression that the repaired binding is meddled with, instead of recognising the distinctive slotted method and thus the provenance. By contrast, the damaged spine of the binding in Fig. 1 invites the user to examine the different materials that are visible. Its construction is sound enough to support the textblock and allows careful use in the reading room; a box protects the binding in the stacks.

Broken but not unstable

In some cases the damage may appear quite severe when in fact the structure is sound and the covering material is not at risk of further loss. The parchment-bound books in fig. 2 are an example of that. The damage is typical of bindings that suffered from too much UV-light on the spine, which caused the material to deteriorate rapidly while the similar materials in the joint and over the front and back covers were not affected.

From a book-historical point of view, a new spine would not add anything: it is clear that the original binding was a laced-on full parchment cover. Instead, a new spine would cover up all the information now visible on the spine of the bookblock. Zooming in, we can see the sewing structure and the different materials that are used as spine-linings. For the book on the left, parchment fragments with musical notation were used. For the one next to it, strips of block-printed textile were applied between each sewing support to strengthen the structure. The two volumes on its right side also show the use of block-printed cloth. However, in this case the bookbinder economised – these books are only small, after all – and applied only one lining strip to each volume.

What we can also see in Fig. 2 is that the binder pasted these strips, apparently arbitrarily, between the first and second sewing support in one instance, and between the second and third in the other. This is all the more interesting because the book on the far right displays a very intentional application of materials. Here we see two kinds of materials, cloth and paper. The blue striped cloth is used at head and tail, where strength of material is important to support the endband sewing, and in the middle. The paper strips with their reddish blockstamped decoration are used above and below the central cloth strip, where strength is a little less important. Thus, the structure is well balanced, not unimportant for a book of this size and weight.

This case shows how it is sometimes better to do nothing, or to simply consolidate the condition (e.g. stabilising the damage, making sure that it cannot become worse) without actually repairing the damage. In the case of these parchment bindings, leaving the damage benefits the user and the book itself. Without the rather rigid parchment spine of the binding the book opens more easily and thus its readability improves. This means that the user will not have to put any pressure on the joints when reading, and therefore the book’s structure will hold. A new spine would change the balance and might cause damage to the weaker areas such as the joints, which are currently unbroken. As a by-product of the decision to do nothing, the conservator saves time, which can be invested in those books that are at risk of progressive damage, or are damaged in such a way that their broken structures currently do not allow for use.

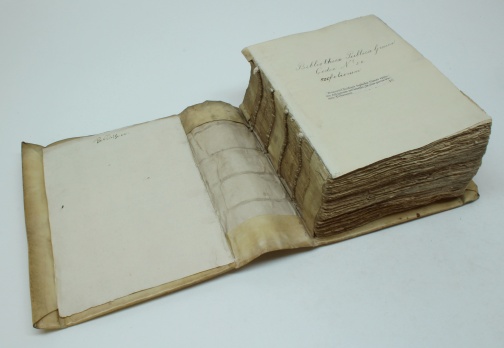

Too thick to function well

Different binding types have different characteristics, and the materials and techniques used to construct the book influence the objects’ physical properties and its ‘mechanism’. A leather covering, for example, pasted onto the spine of a manuscript, supports the textblock spine when the book is used. A parchment binding that is laced on to the textblock with the binding supports, but is not actually connected to the spine itself, moves away from the textblock spine when the book is opened (visible in Fig. 3) When, in addition, the spine of the binding is stiff and the textblock spine is flexible, a tension occurs which strains the joints. The Greek manuscript in Figs. 4-6 is an example of such an unfortunate combination. One of the joints gave way: the book’s solution to the problem. A conservation treatment aiming to restore the broken joint would only inflict further tension on the other joint and eventually lead to more damage and a repeated intervention. It was therefore decided to leave the damage as it is. The manuscript is accessible and safe to handle, though its uncommon condition may raise some questions at first encounter.

These examples show that damage is not always a problem that needs to be solved. They do not, of course, represent all conservation issues, or every reason for choosing not to treat damage. However, if they inspire the reader to think about physical characteristics and the sensitive condition of an old volume, these objects already serve a purpose that a completely restored volume would not.

I really enjoyed a lot.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on sokol çunga.

LikeLike

Thank you for your thoughtful and intriguing response. It makes me happy that medievalbooks.nl is enjoyed so much and that it even serves to open up the past – a past beyond the bookish world, even. I, for one, feel that the book historian should aim to understand and place the object of study – the medieval manuscript – in its cultural setting of production and early use. Knowing that these “alien” objects were once handled and enjoyed by individuals like us, yet a thousand years back, is a strong drive in my work as an academic. If one would want to be romantic about it, one could remark that we owe it to the individuals who produced these objects that we make sense of them. And so I try.

LikeLike

I am, in one sense, an amateur historian. But in another sense, I incorporated history into my professional life, to understand past human processes that led to current conditions. I was an environmental analyst who worked with government agencies and local communities to make decisions about managing natural resources. That may sound far removed from the topics you write about, but it is not, to my mind. A necessary part of my work was to guide the people I worked with to an understanding of the historical dynamics of whatever problem we came together to address, so that they could create solutions acceptible to a range of modern perspectives . Your columns give insights into the thinking of the people who produced these books, shaped by the conditions of their times. I have learned a great deal from “watching” them make decisions based on practical concerns, and from seeing the personalities emerge through the spontaneous response to problems or opportunities that come up in the creative process. There is a joyful recognition of the same processes I come across in my work and an increased understanding of the people I worked with. I am retired now, but I still write about the issues I worked on, and still occasionally serve as a resource. But now, I can also indulge myself in simply exploring for the pleasure of learning more about things that have always fascinated me- including getting to know people of past centuries. Thanks for your column for being a delightful conduit for that past-time.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on nellindreams.

LikeLike

I was so pleased to see this post! Last summer I went to the Seminario Barbarigo at Montefiascone to take a class. (These classes support the conservation of the seminary library.) We studied the history of Italian printing and binding in the early sixteenth century, and also reproduced a slotted spine binding. It was fantastic, and I learned so much! Very interesting post, thanks so much!

LikeLike

FASCINATING POST!!!

I enjoyed it enormously, thanks a lot for sharing these thoughts and congrats for such a nice text.

LikeLike

Look forward to reading it !

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Progressive Rubber Boots.

LikeLike

Great to hear you enjoy the posts. I’m trying to publish one more this year.

LikeLike

My first post failed to appear! So I’ll try again! Thank you this was a fascinating and very informative post. As with previous comments -I have wondered whether ‘repairs’ are always the best thing.

I am gradually working my way through all the blogs . I’m enjoying them very much.

LikeLike

Oh, I love this so much! I’m so crazy about old books. History often proved to be a warped image of the truth, a sort of journalism. Access to medieval books is a treasure in many ways.

LikeLike

What an intriguing and very informative read. Thank you so much. I’m in the process in reading your archive ones too. Im very interested in textiles and their use and how and why they are depicted in MS .

LikeLiked by 1 person

As both book conservator and a book history student, this is exactly what worries me at times when I hear about some book restoration projects! It’s great to read something about it.

I also admire your other research, I even quoted you in my thesis!

LikeLike

In my experience, the collaboration is extremely useful. Thanks for reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Alexandra Vidal and commented:

Very good article!

LikeLike

Wow ! This is the kind of post that you do not expect to find, very happy to see collaboration between conservators and scholars. We should have much more

LikeLiked by 4 people