Do you leave your e-reader or iPad on the table in Starbucks when you are called to pick up your cup of Joe? You’re probably not inclined to do this, because the object in question might be stolen. The medieval reader would nod his head approvingly, because book theft happened in his day too. In medieval times, however, the loss was much greater, given that the average price of a book – when purchased by an individual or community – was much higher. In fact, a more appropriate question would be whether you would leave the keys in the ignition of your car with the engine running when you enter Starbucks to order a coffee. Fortunately, the medieval reader had various strategies to combat book theft. Some of these appear a bit over the top to our modern eyes, while others seem not effective at all.

Chains

The least subtle but most effective way to keep your books safe was to chain them to a bookcase. Walking around in a “chained library” is an unreal experience (Fig. 1). There is nothing like seeing a medieval book in its natural habitat, where the chains produce a “cling-cling” sound when you walk too close to them – a sound that must have been familiar to medieval users of chained libraries.

While there are only a modest number of chained libraries still in existence today (in my own country just one remains, Fig. 2), many of the medieval books we consult in modern libraries were once part of such a collection of “imprisoned” books. Objects that were once chained can be identified with ease, either from the attached chain (Fig. 3) or from the imprint it left in the wood of the book binding (example here, lower edge). The links of the chain are remarkably crude and clunky, although they have a certain charm as well (Fig. 4 and image all the way at the top, taken from this source).

The primary reason for chaining a book was, obviously, safekeeping. Just like phones and tablets on display in modern stores are fixed to their display tables with straps, these precious medieval books were bolted to the library that owned them. This feature of stabilitas loci (to allude to the Benedictine ideal of staying in one location your entire life) turns the chain into something interesting beyond the strictly book-historical. It shows, after all, that the text inside the object was available in a public or semi-public place, such as a church or a cathedral. In other words, chains (or traces of them) suggest how information was accessed.

Book chests

Not all chained books were part of a real library – say a room with one or more bookcases. The famous seventeenth-century “Gorton Chest” from Chetham’s Library shows that books were also chained inside a book chest (Fig. 5, more here and here). This particular example was made in 1658 to contain 68 volumes that were purchased from the bequest of Humphrey Chetham. The lot made up the full extent of the parochial library of Gorton Chapel.

While book chests were a common phenomenon in medieval times, most of them did not actually feature chains. Surviving specimens suggest that the majority were merely wooden boxes, often enforced, that were fitted with one or more locks. The one that still survives in Merton College library, dating from the fourteenth-century, is a good example of such an object (Fig. 6). The theft-prevention plan of these chests was simple yet effective: the filled object was too heavy to move or steal, while the locks kept the contents safe from theft. In a sense, the heavy and enforced chest is the equivalent of a modern safe. Similar chests were used for other kinds of precious objects as well (here is one not made for books).

Cursing

Considering these two practical theft-prevention techniques – chaining your books to something unmovable or putting them into a safe – the third seems kind of odd: to write a curse against book thieves inside the book. Your typical curse (or anathema) simply stated that the thief would be cursed, like this one in a book from an unidentified Church of St Caecilia: “Whoever takes this book or steals it or in some evil way removes it from the Church of St Caecilia, may he be damned and cursed forever, unless he returns it or atones for his act” (source and image). Some of these book curses really rub it in: “If anyone should steal it, let him know that on the Day of Judgement the most sainted martyr himself will be the accuser against him before the face of our Lord Jesus Christ” (source).

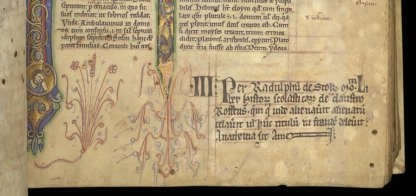

Book curses appear both in Latin and the vernacular, including in non-Western traditions, like Arabic (example here). Fig. 7 shows an Anglo-Saxon curse from the second half of the eleventh century, in a manuscript donated to Exeter Cathedral by bishop Leofric. This combination (of curse and donated book) is encountered more often. The inscription at the bottom of the page in Fig. 8 notes that the book was donated to Rochester Priory in Kent by Ralph of Stoke. The notation ends with a short book curse.

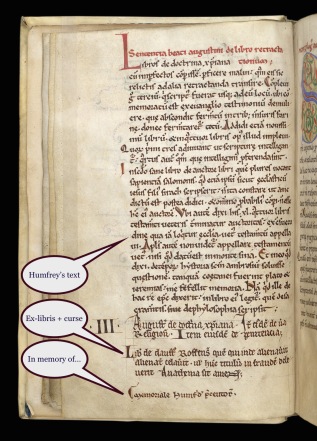

These two cases suggest that the receivers of the gifts felt compelled to treat the given object with extra care. A similar sentiment is encountered in some books that were copied by individuals who were, for some reason, important to a religious house. In the early twelfth century, one Humphrey was precentor in Rochester Priory, Kent, meaning he lead the congregation in singing during the mass. He is also known as a scribe who copied a number of books for the community in a particularly dazzling script. One of these books he copied bears a curse as well as a note “In memory of Humphrey the precentor” right below it (Fig. 9). The apparent significance to the community may well be the reason why a curse was added.

Optimism

Book curses raise a lot of interesting questions. Were they indeed favoured for books of special significance? Are we to understand their presence as a sign that librarians and book owners really thought the inscriptions were effective? And if they were, why not place them in all books contained in the library? No matter the answers to these queries, there is a certain optimism embedded in such notations: the writer of the note apparently believed that a gentle reminder would bring potential thieves around and they might consequently not take the object.

Interestingly, the same optimism is echoed by inscriptions that ask the finder or thief of a book to return the object to its rightful owner. A Middle English note reads: “Ho so me fond er ho so me took I am // jon Fosys Boke” (Whoever found me or whoever took me, I am John Foss’s book) (Fig. 10, information taken from this article).

Notes like this bring us back to Starbucks, where I have seen similar requests stuck to the wall: whoever took my iPad, please return it, or at least return the files on it. Just as in modern times, medieval books were likely also not often returned. In fact, the example of John Foss’s book gives us reason for pessimism: in the inscription the name is written on erasure, meaning that an earlier name, of a previous owner, was erased with a knife. Curiously, this makes John Foss the potential thief of this book. If this is indeed the case, the thief identifies himself by altering the very book curse that was aimed at people like him.

Post-scriptum: more on chained libraries in this post and on the one in Zutphen here. The link to the image of the curse related to the Church of St Caecilia was provided by Elizabeth Archibald (@Elizarchibald).

Thank you so much for your response. I guess in the Middle Age, they had a different approach to reading if, as in Charles V ‘s Louvre library, one faced a library of 1,500 books without titles. I suppose that as books were rare and not known, picking any one of them was rewarding.

Sorry for the delay in my response.

LikeLike

Some have titles written on their front or back. Often there is none.

LikeLike

How can you find the title of a chained book?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on P.A.M. – Património, Artes e Museus.

LikeLike

Mais uma vez republiquei

LikeLike

I read this great post yesterday (8th May 2016) and then visited Wells Cathedral today only to find that it too has a chained library built in the early 1400s. To top it off, I was permitted to take photographs which made me rather happy.

LikeLike

And yet, for all these measures, some books did get stolen. I wonder whether recovery always was as tenacious as when the monks of Ely cathedral wrote to the king of France in the 1380s to help them retrieve stolen books spotted in Paris.

LikeLike

WOW! I would love to visit a chained library, I find the concept absolutely intriguing.

LikeLike

Fascinating post.

thelonelyauthorblog

LikeLike

My pleasure!

LikeLike

Wonderfully written. A part of history completely unknown to me. Thank you!

LikeLike

I learned about these libraries in the 7th grade, but have never actually seen them until now, nor did I know that some were still in existence today. I also never knew that these were chained via a front or back wooden cover. Thanks for the fascinating read!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on J. Ramsey Golden and commented:

Fascinating read!

LikeLike

An alternative view to chaining books to keep them from theft is chaining books to make them available. Since they were so expensive the chains enabled the books to be more available while preventing theft at the same time. Without chains the books may well have been much less accessible.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Iron-Bound Tome and commented:

An interesting article on securing books against theft in medieval times. Chains, curses, and heavy chests all used to protect books.

LikeLike

They probably find it pretty unsafe 😉

LikeLike

This is an extraordinary bit of information! Books were held so sacred back in those times. Indeed, information is power, and perhaps now in our day and age we take it for granted. I have to wonder what our medieval counterparts would think of the Internet! 🙂 Have a great day!

LikeLike

Irosa: more like the medieval version of the FBI copyright warning…

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Three R's Blog and commented:

You will appreciate this fascinating post about how libraries battled book theft in the Middle Ages. I am glad we no longer have to resort to such measures! 🙂

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The eBook Evangelist and commented:

As both a student of medieval studies and avid e-reader enthusiast, I found this one fascinating….

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Blue Ink Asides.

LikeLike

Love the idea of curses on books. LOL! Then again, I write paranormal, so it fits. 😉

Now I’m really tempted to come up with one… *thinking*

LikeLike

Curses were the medieval version of XXI century DRM.

LikeLike

That’s right: through the wood of either the front or back cover.

LikeLike

Really interesting. When visiting the Bodleian Library recently, we heard that the filming of Harry Potter got some historical detail wrong when they chained the book as they chained it to the spine, apparently the chain should have been fixed to the front cover.

LikeLike

Thanks for that – appreciated!

LikeLike

I found this too. The Cages of Marsh’s Library, Dublinhttp://dublincitypubliclibraries.com/dublin-buildings/marshs-library

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been to Hereford Cathedral and seen the chained books. The smell of them, and the realisation that they are indeed (and always were), rare and great treasures is intoxicating.

The work that went into them, the hours spent writing out the words, and the damage that precious work must have caused to the (generally) monks’ eyesight is very humbling.

We are so lucky to be able to read whatever we want, whenever we want to – to have access to libraries (physical or electronic), where we can inform ourselves and enrich our understanding of the world we live in in ways that were far beyond our ancestors’ reach.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you got acquainted to these measures!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is very interesting and informative love this. Had no idea they did this! Thanks 🙂

LikeLike

Reblogged this on My Link Pile.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on – A Mad Garden Party – and commented:

Sometimes I feel that my books are my lifeline. Had I lived in Medieval Times I probably would have needed a vault or guards to protect my books!

LikeLike

Ah, entranced I am as well! Some libraries (at least ours) still attach current issues of magazines and newspapers to long, awkward post-like affairs to discourage readers from stuffing in coats or whatnot and running off with them. I’ve known of chained libraries since I was young. Chained books are akin perhaps to the “laptop cables” one sometimes sees these days. I lost a new laptop and portable printer to a burglar some years ago, but a cable would not have protected them. I had not thought of curses. I think I will put one on my tablet. It slips handily into my bag when needed, though so a curse might be superfluous. MIght be useful for those books my friends carelessly overlook returning, though! Thinking up a contemporary curse using medieval wording should be fun.

LikeLike

You are welcome, I am just an ordinary book lover but am entranced by your blog.

LikeLike

Oh, this is fascinating. I had never heard of the chained libraries before (horror movies should take note of this) but I’m hardly surprised with the curses. Back in Roman times they would inscribe curses on tablets and the like and offer them to the Gods so to punish thieves, you can see them at the Baths in Bath, UK.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on RANDOM MAGIC and commented:

Just what the doctor ordered while I plan for my classes in the fall! 🙂

LikeLike

Sixtus V put out a notice that any person of whatsoever status (that means you, Cardinal) who removed a book from the Vatican Library without his own express permission was excommunicated, banned not just from the library l(ike someone who smokes in the bar) but from heaven.

LikeLike

Thanks for that comment!

LikeLike

Thanks for that Laura. I did see some of those combos. Odd, as if they didn’t trust the strength of the chain.

LikeLike

Glad this post introduced you to the fascinating chained library. There are still some around in Europe; only a plane ride away!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have followed this blog for a while now and just wanted to say how much I enjoy it. This was a particularly interesting blog post. I just wanted to say that in the Devon village where I grew up, the wheelwright and smith made carts for both tractors and horses, and made similar rough looking chains for them. They were made on an anvil with small hammers, so had this handmade look.

LikeLike

Fascinating!

LikeLike

Great post. I especially like thinking of chained books and book curses together. If anyone wants to find out more about the chained book shown at the very beginning of the blog, there is a full description at http://textmanuscripts.com/manuscript_description.php?id=3373&%

LikeLiked by 1 person

“If anyone should steal it, let him know that on the Day of Judgement the most sainted martyr himself will be the accuser against him before the face of our Lord Jesus Christ”

I love it! If I had the time, I would inscribe all of my books with this.

LikeLike

This is so fascinating! I’ve never heard of chained libraries, but it totally makes sense. I’d love to go to one, though I’d probably not be able to read a word in any of the books; I just love old books. Unfortunately, living in the U.S., I’ve never held a book from earlier than the 1850s. I really do envy Europeans on their long, documented history 😀

Thanks for another extremely interesting post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting and informative

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Old Squeaky Shoes.

LikeLike

Very interesting read. Many thanks.

LikeLike

You might want to ad excommunication to the list. In Salamanca you can buy contemporary copies of a late-medieval text that was put up in the library stating that anyone steeling a book is excommunicated by the fact itself. I have no idea on the effectiveness of the measure.

LikeLiked by 2 people