A word of warning: this post may make you want to weep. Last week I blogged about tiny pieces of parchment, paper birch bark, and wood that were filled with short messages from individuals in Antiquity and the Middle Ages (check out Texting in Medieval Times). The snippets – from a soldier’s request for more beer to a duke’s shopping list – were made cheaply and with little care because the messages on them were not meant to be kept long. Although such ephemeral material doesn’t normally survive, it forms an important historical source: it provides a rare glimpse on everyday life in medieval times.

More than in any other medieval document I have seen, such an intimate view of medieval life is provided by a type of written object I encountered for the first time this week (Fig. 1). When visiting the restoration lab at the regional archives in Leiden (Erfgoed Leiden en omstreken) my eyes were drawn to a photograph on the wall that showed a tiny strip of paper from the fifteenth century. I returned the next day to order up the slips from the vault and see for myself what they were all about. Here is the powerful story of a collection of medieval name tags, which may be best consumed with a tissue handy by.

Name tags

The fifteenth-century strips are written in Middle Dutch and kept in the archive of the medieval Holy Spirit Orphanage in the city of Leiden (Dutch: Heilige Geest- of Arme Wees- en Kinderhuis). Founded in 1316, the orphanage was connected to the parish of St Peter (more here). The building is still there and is situated less than 100 meters from the massive Church of Hoogland (Hooglandse Kerk), which can be seen towering over the city from miles away. Until the middle of the twentieth century, the charitable organisation was responsible for the care of foundlings and children.

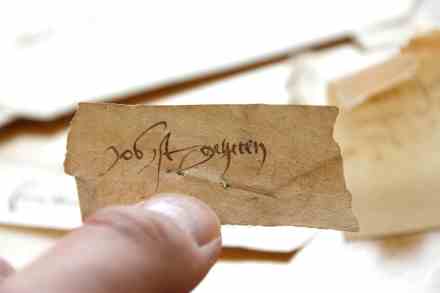

The paper slips, some of which are as small as 10×30 mm, add a real-world dimension to what we know about medieval orphanages. The examples above read: “This child is named Bartholomew” (Fig. 2: Item Dit kint heeit bartelmeis), “Job is his name” (Fig. 3: Job ist geheten), and “This child’s name is William” (Fig. 4: Dit kint hiet Willem). Each slip shows a pair of holes as well as the indent of a pin, which explains what we are looking at: name tags pinned on foundlings’ clothing as they entered the orphanage. As far as I know, this is the only surviving collection of medieval name tags, and it is a mystery why they were kept in the orphanage’s archive for five centuries.

Who wrote them?

The tag collection can probably be divided into two categories. Some were probably written by one of the masters of the orphanage. The ones seen in Figs. 2-4, for example, are done by an experienced, professional hand. Others, however, are written in a less experienced hand. These may well have been written by the parents. This is supported by the observation that these tags provide more details about the child (Figs. 5-6).

The one seen in Fig. 5 (again with a clear pin mark) reads: “This child is called Cornelius and belongs to a painter whose wife is a wool comber” (Dit kijnt heet cornelis dit hoet een schilder een schilder toe sijn wijf is een kemster). On the tag in Fig. 6 we read “This child is baptised and her name is Mariken” (Dijt kijnt is ghekorstent ende haerren name is mariken). Both show how some children – whether found in the street or dropped off at the orphanage – entered the orphanage with some family history attached, literally.

The only parchment tag provides a particularly detailed history (Fig. 7). It reads “My mother gave me an illegal father, which is why I was brought here as a foundling. Keep this note so that they can pick me up again later. I was baptised and born on St Remigius day.” (Mijn moeder min een onrecht vader gaf daer om ben ic voer een vondelinck gebracht, bewaert dit briefken v[…] opdat nae min weder halen sal ic ben gedopt ende op Remigius dach geboren.) As in the case of Fig. 5-6, it is very likely that the information on this note was provided by the parents, probably as they dropped off their child.

Accompanying booklet

The ten or so surviving slips are kept together with a fifteenth-century booklet, in which they may, in fact, have traveled through time. The title on the first page tells us what we are dealing with: “The Child Book: How the Children Came Here” (Fig. 8: Item dat kijnderbock hoe dat die kijnder hier ghecomen sijen).

The booklet forms the counterpart to the labels, for it registers the orphans and provides information about the location where they were found. We may presume that the foundlings entered the house, often as babies, were tagged, and then processed. However, the entries in the book also contains brief reports from individuals who found foundlings in public spaces and came by to drop them off at the orphanage. The stories on the fifty-odd pages are truly heartbreaking.

On page 33 the following entry is found (Fig. 9). “Item, a child came to us without a name on the Thursday before the feast of St Peter in Chains. And we named it Peter, in the year 1502, for he was found in the Church of Our Lady under a bench.” (Item ons is en kijnt an ghekoemen sonder maem des donnersdacx voer sijnte pieters dach ad vynckula [St Peter in Chains] ende vij hietten pieter int jaer [1502] ende vas gheleit in onsser frouwen kerc onder een banck).

On page 7 a story with unhappy ending is penned down, by two scribes under the heading “anonymous” (sonder naem) (Fig. 10).

The first writes “Item a child was found in the church of St Peter and we named it Luke, on the Sunday before St Luke [= 18 October] in the year 1491. It looked like a newborn child to us, and it had been placed on the altar of St Agnes.” A second hand, in a slightly browner ink, added a short line, sometime later: “Luke died around St Catharine’s day [= 25 November] in the same year.” (Scribe 1: Item een kijnt ende vas ghevonden in sinte pieters kerc ende wij hietent Lucas op die zonnendach voer sinte Lucas anno [1491] ende was een nuo borun kijnt als ons dachten ende lach op sinte aegten altaer. Scribe 2: Lucas starf omtrent sinte katrinen dach actum voerseit.) The second scribe then crossed out the entry in the register.

These narratives form a powerful accompaniment to the paper slips. They report how and where the foundlings were found, and when they came to the orphanage with a paper name tag pinned on their clothes. Handling the paper slips in the archives is a heartbreaking experience: to think that they were made for the sole purpose of providing information about a child whose life was about to change dramatically. The handwriting underscores the emotions that must have been felt by the parents: the text is written in a scruffy manner, often with mistakes in spelling and grammar. For them it must have been a difficult task to write down these mini histories, in more ways than one.

Postscriptum – More on the history of the orphanage in Kees van der Wiel, ‘Dit kint hiet Willem’. De Heilige Geest in Leiden – 700 jaar vondelingen, wezen en jeugdzorg (Leiden: Primavera Pers, 2010), which also features some of the slips. With many thanks to Erfgoed Leiden for letting me photograph the name tags and use them for this post; and to Ed van der Vlist (Royal Library, The Hague) for his help with some readings. Just to emphasise, while I studied and transcribed them, I did not discover the tags, which featured in an exhibition some years ago.

You are welcome. Have fun digging in the past!

LikeLike

Erik, I recently found an ancestress who was a foundling (born around 1805). She was married in Zegwaart and on her marriage record, it was noted that she was a foundling…it did include her parents’ names, but I think they were adoptive parents, since they had different last names from hers. I was trying to find out more about Dutch foundlings and found your site. Fascinating. I am hoping to find more about my many times G-Grandmother. I will continue to try to find more information about foundlings in the Netherlands. Thank you for this post.

LikeLike

“My mother gave me an illegal father.” So poignant, as though the child blamed the mother. Society speaks, here, through the centuries.

LikeLike

I agree, the tags do invite creating a good story around them, in part because of their brevity, but also because they provide the perhaps most personal of details regarding their carriers: their names.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just so enjoyed this post. I am a story-telling, rather than a historian, and wonder at the vast and deep stories behind each of these name-tags…as you said in an earlier reply, not only the stories of these children but of their parents and the vast array of circumstances that led each child to the door of that orphanage.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks

LikeLike

http://foundlingmuseum.org.uk/exhibitions-collections/exhibitions-displays/past-exhibitions/ …scroll down the page to find a wee bit of info. there was a really good webpage with music a couple of years ago, that may still be there somewhere.

LikeLike

Thanks for that. I was alerted to these slips by someone else but have not yet been able to trace them. With your extra details I will have another search. Thanks!

LikeLike

I meant to say the Foundling exhibition archive complements this collection of name tags, poignant and painful, and so deeply human.

LikeLike

Erik, a couple of years ago I heard about an exhibition called Threads of Feeling, textile tokens from the London Foundling Hospital. The names of the children who came to this place were recorded along with a snippet of cloth from their own or their mother’s garment. The register dates back to 1745, and the cloth bits are a wonderful and poignant archive (that also serves to illustrate common cloth, the day to day stuff that is largely missing from records). There was a good online introduction to the exhibition at the Foundling Museum’s website.

LikeLike

You are welcome. Thanks for your kind remark.

LikeLike

You are welcome – thanks for visiting!

LikeLike

Thank Marc. I had the same initial reading (an exuberant bretzel s) but opted for the b because the ascender seemed a better fit for that letter. Happy to change it if you think this kind of s does appear with such a high ascender.

LikeLike

These couldn’t be other than deeply moving; thanks for your beautiful, learned, caring presentation.

LikeLike

Fascinating, thanks Eric.

(PS “Jos” rather than “Job”)

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment Ramona!

LikeLike

Ja, die had ik reeds in eerdere versie verbeterd, maar die correctie is (met andere) door synchronisatieprobleem terug van weg geweest. Bedankt!

LikeLike

Wow, I never knew these existed! As you say, it is heartbreaking to think of the circumstances in which these tags were produced.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Archives Mouse and commented:

This is a very interesting look at ephemera and the stories it can tell!

LikeLike

De kerk 100 meter vanaf het weeshuis is niet de Pieterskerk, maar de Hooglandse Kerk.

LikeLike

Possibly. There are two tags with such a series of tiny holes in them. It might seem too elaborate to stitch a paper on (rather than just pin it), but then again that may just be the explanation of the holes. Thanks for your input.

LikeLike

It looks like the tag on Fig 6 could have been sewn to a piece of cloth, don’t you think ?

LikeLike

Bedankt voor je aardige reactie. We zouden eigenlijk meer van dit soort briefjes moeten vinden en bestuderen om die vraag te beantwoorden, maar ook hoe arm mensen eigenlijk waren die kinderen ter vondeling legden. Schrift en spelling kan zeker helpen je interessante vraag te beantwoorden.

LikeLike

…wijder verspreid….

LikeLike

Wat een prachtig verhaal. Ik vind het elke keer weer bijzonder hoe u de gewone middeleeuwer wat dichterbij brengt. Ik heb het via Facebook gedeeld.

Dit verhaal bengt me wel bij de vraag: als deze ouders een briefje konden schrijven, met of zonder vele taalfouten, was de schrijfvaardigheid onder de armeren dan toch weider verspreid dan algemeen wordt aangenomen?

LikeLike

Your reading is correct: I have updated the post. Thanks so much for the correction!

LikeLike

Let me have a look into it. The reading I proposed is not unusual in manuscript colophon.

LikeLike

The normal numbering system in Leiden’s records is as I said. XV = 15 with a C above it = 1500 en[de] ii = and 2, which is 1502.

I’ ve read the Leiden Archival material through 1575. This is a recurrent way of writing dates, and I’ve never seen what you propose (but, of course, I don’t see it here either, which could simply mean it’s there but I’ve read it my way and not your way).

LikeLike

I could immediately read figure no 2 my name is Bartholomeus too and i was happily surprised with it.Thanks.. Bart

LikeLike

Thanks, also for you comment! I am reading 500 (‘v’ with ‘c’ above it) minus 10 (‘x’ in front ‘v’) plus 2 (‘ii’), equals 1492. This fits with the chronology of the book and the dates of the other entries (1491 and 1492). The entries are riddled with unusual spellings, as you can see from the transcriptions, although this may not be one.

LikeLike

Very nice article. Thank you.

Number 9: the date is XV c en[de] ii (1502, not 1492)

LikeLike

You may be right. The downside highlighted in the piece is related to the family drama behind these foundling cases.

LikeLike

Bedankt, je hebt helemaal gelijk. Een muur van die kerk staat er nog. Ik heb het aangepast.

LikeLike

good topic

LikeLike

Bij fig. 9 vertaal je “onsser frouwen kerc” als “church of St. Peter”. Moet dat niet “church of Our Lady” zijn?

LikeLike

A lovely little piece. I wonder, though, why so many commentators assume that these foundlings were disadvantaged by being such? They had a roof, food, clothing, care and almost certainly education. In some cases they would have had better, possibly longer, lives because of being given up by their parent(s) than if they had stayed with them. I wonder if we are programmed to think of Victorian workhouse conditions when we hear about orphanages and foundling homes, because of literature (‘Oliver Twist’, for example) and the fact that they only get mentioned in the media in a modern context when they fail the children in their care?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on My Life.

LikeLike

Interesting post. Poignant materials. Many a slip.

LikeLike

Triste y hermoso a la vez… gracias!

LikeLike

Thanks for your nice comment.

LikeLike

You are welcome – the slips really impressed me when I looked them. I felt I just had to write about them.

LikeLike

Tragic and extraordinary – it’s so rare to catch a glimpse of childhood, sad that it has to be heartbreaking. Thank you so much for this. You do them honour with this post.

LikeLike

I’m a medievalist and an adopted child who was found in circumstances similar to these children — I found your post deepling moving. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Eric: I do enjoy your posts so much and am in awe of your knowledge and computer skills. Most of the children described on the medieval name tags are not orphans, but foundlings. We will never know how many were reclaimed, if any.

Met hartelijke groeten,

Trix Bodde

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Word Peddler and commented:

The past several weeks, I have been haunted by the idea of Legacy. I stumbled across this today and read it as I waited for the school bus to collect my own children.

Five hundred years later, these children are remembered. There names still fresh on my lips, this brings me some peace.

Pax.

LikeLike

You are Erik! Forgive my misspelling. My son is also an Erik, born 1 month, 1 week and 500 years after dear Lucas.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for your comment. Sometimes the “other” side of medieval society steps out of the darkness, but it is not often this vivid.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Impressive and very sad! What more is there to say? To think what _might_ have become of these children, had they lived in different circumstances…

LikeLike

And now our brother in Christ, Lucas, is remembered over 500 years later. Thank you for the good work that you do, Eric. You bring the medieval world of ordinary people, not just the kings and queens, to life.

LikeLiked by 3 people