Both medieval manuscripts and their modern counterparts are designed to accommodate human readers. Our two hands can keep an open book under control with ease by applying gentle pressure on the outer margins of the pages. Release the pressure with your right hand and a page lifts up in the air, just enough to conveniently flip it. With a rustling sound it travels from right to left, moved along by an impatient reader that is left in suspense for a second or two. The proportions of the page, too, are designed to accommodate consumption by human beings. Our eyes can handle only a small number of consecutively placed words, no more than eight or so, depending on the size of the letter. As a consequence, medieval page design shifted to presenting a text in two columns rather than one, a transition that occurred over the course of the twelfth century.

This relationship between book design and human anatomy is seen most vividly in a particularly peculiar bookish object that thrived in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: the hornbook (Fig. 1).

This charming device is a primer: a text used by children as they were learning to read. It contains the alphabet (naturally), but also a small collection of short texts, such as the Lord’s Prayer and Hail Mary (more here and here). Its design reflects perfectly how the material format of books was customised for use by human beings: its user could easily grab a hornbook with one hand and hold it up at eye height. With his other hand the user could then duplicate the letters before his eyes. Two important things stand out when one observes the tradition: the variety of materials used to produce hornbooks – which were made of such materials as wood, lead and gingerbread – and its time of invention, which predate the proposed origins in current scholarly literature.

Materials

The heart of the hornbook is text, albeit a very small amount of it. In fact, it may well be the shortest read to survive from the early-modern period. Most hornbooks from that time are made out of wood. The pupil’s “required readings” were printed on a sheet of paper that was subsequently covered by a thin piece of horn for protection – hence the object’s name. The result is a remarkably sturdy object, which you can drop without damaging it, a minimum requirement for something used by young kids.

Several surviving hornbooks show that the device was also used to teach kids to add and subtract. The one seen in Fig. 2, which dates from the eighteenth century, has a nifty add-on: an abacus. This particular specimen shows the end of the hornbook’s development, which appears to have become more sophisticated over time. The one in Fig. 2 contains another novel feature: the sheet of paper can be removed from behind the horn and replaced by another text, which may perhaps even be found on the reverse (here is another example). This late model is rather like an iPad with several apps loaded, one of which can even be updated when needed!

Other hornbooks were made out of even sturdier materials, such as ivory and lead (Fig. 3). The last one must have been particularly cheap and easy to produce, probably with the help of a mould. This specimen shows that the hornbook was subject to mass production, like its cousin, the printed book.

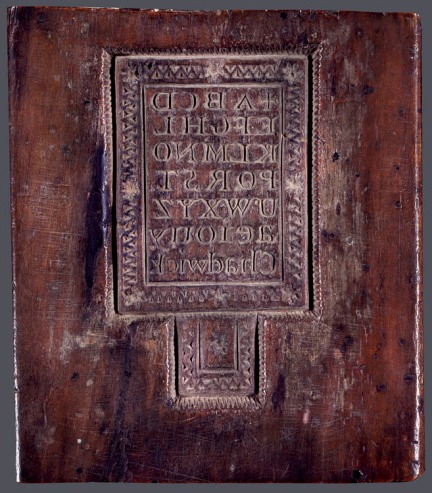

Quite different is the hornbook seen in Fig. 4. This wooden slab could be used to produce a gingerbread hornbook, handle and all. The tradition of this particularly tasty type of hornbook goes back to the seventeenth century. The English poet Matthew Prior (d. 1721) mentions it in one of his poems: “To Master John the English maid / A horn book gives of ginger-bread / And that the Child may learn the better / As he can name, he eats the letter / Proceeding thus with vast delight / He spells, and gnaws from left to right” (source). Although a peculiar book, the gingerbread version of the hornbook probably wins the prize for best didactical tool: what better reward than to eat the letter you were just able to read out loud?

Medieval origins

While the heyday of the hornbook was no doubt the early-modern period, the scholarly literature will also tell you that this bookish device was in used in the fifteenth century, during the late medieval period. In fact, publications on the topic stress that there are also handwritten – medieval – versions of the device. Peculiarly, I wasn’t able to find one, except for this early-sixteenth-century specimen. Even illustrations showing hornbooks “in the wild” date from the seventeenth century at best, such as the pair hanging from the chapman’s basket in an engraving from 1646 (Fig. 5).

So is the hornbook a post-medieval invention? I was about to draw this conclusion, given the lack of evidence predating the early-modern period, when I coincidentally encountered the following illustration in a 14th-century Italian manuscript with an unidentified devotional text about Mary, the mother of Christ (Fig. 6-7).

The image shows Christ being brought to school by his mother. He is bringing his “textbook” to class: a hornbook, which dangles from his wrist by a string, just like many of the later specimens did (see the hole in the handle in Fig. 1). Quite intriguingly, we are shown a real medieval snapshot of how children carried their hornbook to and at school. More importantly, it shows that the hornbook was indeed a medieval invention. Some further digging revealed additional visual evidence of hornbooks being used in before the age of print (Fig. 8).

The manuscript, which was produced in Germany in 1440-1460, shows a teacher holding up a hornbook, using it to show Arabic numerals to a pupil in front of him. The German text bubble next to the scene is very positive about this teaching moment: “With calculus and numbers, I can be a star in arithmetic!” While it was produced somewhat later than the Italian example in Fig. 6, the setting in which the hornbook was used is the same: a context where basic information about letters and digits is conveyed to young pupils. While no actual hornbooks appear to survive from the medieval period, these visual representations show that educating young children was also the driving force behind the production of hornbooks in the age before print.

Reblogged this on Kate McClelland and commented:

I love this blog

LikeLike

Thanks for visiting!

LikeLike

Hi, I am happy to have just found this blog! What amazes me most about this hornbook article is the image of Mary taking Jesus to school. I enjoy Italian Renaissance Art and manuscripts and have looked at many. I have never seen or even thought of Mary taking Jesus to school. We are lucky that the digitalization of so many manuscripts allows us to see so many new images!

LikeLike

Thanks for visiting – and for the link!

LikeLike

Really enjoy reading your “stuff.” You have a fascinating blog. I’m a book artist (make books and books as art) and get ideas from you and medieval books. Will have to try the horn book! (My book art web site: judyfolkenberg.com)

LikeLike

Very interesting. Hornbook like a simple iPad ..well, sort of. Or iPhone. Yea, I dared to say that.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Scribe Scribbles and commented:

This is a fantastic article on an item used for education that is especially relevant for children. I think this would be a fantastic item to add to a medieval/pre-modern setting.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on aichaaicha.

LikeLike

Great to hear!

LikeLike

That’s a hard one as there are many “typical” dividers, depending on the background of the scholar. I am inclined to take c 1450 as a divider, because that is when print comes in – almost.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am reading your blog since a year or more and I love it. Chapeau my good man.

LikeLike

When I started school in Wales, slate and chalk had only recently been replaced by paper and pencil; how I wish we had had gingerbread since I seemed to be perpetually hungry.

LikeLike

Great post as always! Could you clarify where/when scholars typically delineate the medieval era from early modern?

LikeLike

Fascinating. Love the gingerbread hornbook idea!

LikeLike

Thank *you*!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on 장안동오피「girlie」밤전건마 and commented:

amazing

LikeLike

I am very glad to hear you enjoy the posts. It makes it fun for me too, to know that they are being enjoyed. Thanks for your comment!

LikeLike

There is modern research for this, but it has not been tested on medieval books. The number of words is my own count (not published). Significant work is needed here.

LikeLike

I completely love your blog, and often share it. Thank you.

LikeLike

As a semi-retired book conservator it is a pleasure to read your posts. I am learning despite my age. Thank you for devoting some of your time to keeping all of us out here on the infobahn informed and amused.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Fascinating post as usual — thank you! I’ve often wondered about text presentation in multiple columns rather than page width, and am intrigued by this note: “Our eyes can handle only a small number of consecutively placed words, no more than eight or so, depending on the size of the letter.” Can you point to some sources for this?

Cheers!

LikeLike

That’s just great to hear!

LikeLike

Thanks – it’s my silly autocorrect – and my not spotting it, of course! (I try to post every week, but at least once every two weeks.)

LikeLike

Your blogs are always interesting. You are on my scribal “favorite links” list.

LikeLike

I learn so many wonderful things from your blog that I look forward to reading the next one as soon as I finish the latest installment. Thanks!

(There is typo in the discussion of Figure 5 – seventieth for seventeenth. I hope you’ll excuse my presumption in pointing this out.)

LikeLike

Thanks for visiting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sooooo interesting!!! Thanks a lot

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Writing Reconsidered and commented:

As a professional writer, I’m often asked what I think of the changing face of the publishing industry. Do I want to find an agent? Do I want to self-publish? Go strictly e-book? Publish “traditionally”? Really though, the question they most want to ask is: “Are books dying out?”

My answer to this is always a laughing “no,” simply because–while the industry is certainly changing in many ways–books have always been (and will always be) at once a source of both function and art. In this post from Medieval Books, we can see evidence of this fact in the simultaneously artful, creative, and intensely functional style of different ancient books.

Today, as the internet changes our needs, demands, and expectations of books, we are also beginning to see a return to the production of artistically crafted books–that is, books produced as works of art in and of themselves. The content, in this form of publishing, thus becomes art encased in art. For just a few examples of this growing trend, check out: Anteism, Publication Studio, and Art Metropole.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You improved my plan! Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Especially when you go with the gingerbread version!

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is fantastic! I realize that not all medieval children were educated, but those that were received a more thorough education on one hornbook than many children today on an iPad. Yes, when I am a grandmother, all my little ones will receive… hornbooks! I’ll be so popular! 😉

LikeLiked by 2 people

this blog is a big resource! Great blog!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s really nice to hear; thanks for letting me know.

LikeLike

I enjoy your blog enormously!

LikeLiked by 1 person