Books in use generally reside in our hands or on our desks. This was not very different in medieval times. However, medieval and modern reading culture take different paths when it comes to books that are not in use. While both then and now the objects are commonly shelved after use, medieval readers had additional storing options: slipping the book into a box, bag or wrapper. Unfortunately, few of these exotic – and fascinating – storage devices survive today. However, the ones that do indicate that many were made with a specific purpose in mind, namely transportation. Here are some popular means of packing up your book to go in medieval times, including the precursor of our modern tablet sleeve.

Box it

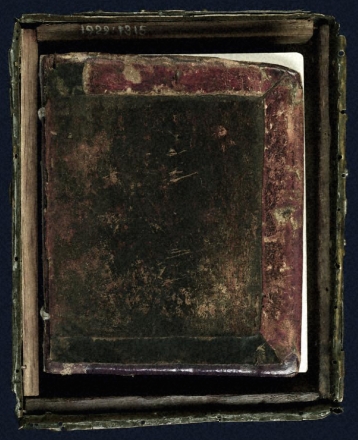

The book box is probably the sturdiest and most effective means to protect your book against the elements and other hostilities on the medieval road. Such boxes were usually made out of wood, to which ornaments, gems and even ivory cuttings were attached, commonly with nails. A particularly well preserved example is seen in Fig. 1. The box contains a famous book of hymns from St Gall, which was designed to be carried in processions both within the monastery and through the nearby city of St Gall. My recent post on “slim” books showed the actual book found inside this box, a narrow object designed to be held in one hand (post here, image here).

Decoration on the outside of the book box not only made the object look pretty, it also gave it prestige. In fact, ivory cuttings and shiny gems reflected the importance the book had within a monastic community or a church. Book boxes actually bear a striking resemblance to medieval reliquaries, shrines or containers made for holding a relic such as the arm of a saint (example here) or a splinter of the holy cross (here). One type of book box in particular matches this profile very well: the Irish cumdach or ‘book shrine’ (Figs. 2-3).

The cumdach often held a small manuscript. The Stowe Missal for which the cumdach in Fig. 2 was made, measures only 150×120 mm, which is a little higher than the iPhone 6 (and a little smaller than the iPhone 6 Plus). The book is very snug inside the box (Fig. 3). The small size matches the object’s anticipated use. The Irish cumdachs were often carried around the neck of a monk who would run up and down in front of the troops right before battle. The book became a charm of sorts, which was to bring fortune in battle. It made good sense to store this ‘secret weapon’ in a sturdy box that could withstand all that bouncing around and even a potential blow of a sword.

The most famous of these is the sixth-century Cathach of St Columba, which holds a Psalter from the sixth or seventh century. Curiously, while this cathach (‘battler’) is commonly regarded as an object meant for carrying into battle to ensure victory (source here), it is obviously too big to carry around one’s neck: it measures 270×190 mm and weighs quite a bit. Its user probably ran up and down the battlefield with the book under his arm. Taking your book to battle in a protective box remained popular throughout early-modern history, as shown by the “field Bible” of c. 1700 , which was taken on war campaigns by king Charles II of Sweden (Fig. 4).

Bag it

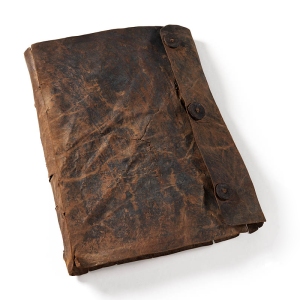

The satchel was another means to carry your book around in the medieval outdoors. They were made of leather and commonly decorated in the manner seen in the famous 9th-century Book of Armagh – which, curiously, has a modern lock (Figs. 5-6).

Very few such satchels survive but we get an inkling of their use and popularity through medieval texts. A seventh-century tract instructs monks to “Hang your white booksacks on the wall, set your lovely satchels in a straight line” (source). It suggests that each member of this particular community owned a satchel. The same text also explains from what animal the leather came (sheep) and how the skin was turned into a bag: take a square piece of leather, sew it closed except for a single opening, which should be closed by a cover fitted with knobs.

In 2006 a particularly old specimen was found in a bog, where it had been resting for 1200 years. Around 800 someone had a portable Psalter made, which came with a leather satchel. Somehow the book fell into the remote bog at Faddan More in north Tipperary, Ireland. Restoration revealed a plain but charming example of an early-medieval book bag (Fig. 7). Because it does not feature a strap, this type of satchel bears a striking resemblance to our modern tablet sleeve: unbutton the flap, slide in your reading device, and be on your merry way.

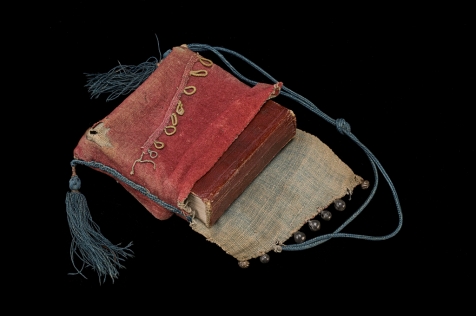

Like book boxes, satchels had a life far beyond the Middle ages. Fig. 8 shows a 17th-century specimen made of cloth that holds an Arabic devotional book. It belonged to a Turkish soldier captured by Venetian forces in 1668. Like the book box, this charming piece of ‘apparel’ carried a religious text into battle, although in this case the book was likely meant for private reading rather than as an aid to victory.

Wrap it

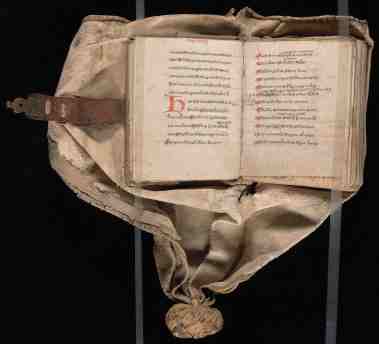

If you wanted to carry your book on your body instead of in a box or bag, for example because you needed to consult the text frequently, the girdle book was your device of choice. The binding of these books came with a wrapper, which kind of flows from the leather of the binding itself. It allowed the user to wrap the manuscript into the leather, which produced a watertight package. A knot was attached to the end of the wrapper. The carrier of the book slipped it under his belt so he could carry the book on his body. Many of these girdle books are small and light objects, which made it easy to dangle the package from your belt. A particularly well preserved specimen in Yale’s Beinecke library shows how well such wrappers protected the book (Figs. 9-10).

This particular book was written in England during the fifteenth century, though the binding may be continental. It measures only 100×80 mm (a little bigger than a credit card) and contains Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy, a sixth-century text discussing such topics as free will, virtue, and justice. These may not be the usual topics to have ready at hand while walking the streets of a late-medieval city, but someone found such use important enough to have it made portable – and at the ready at all times.

Other girdle books were objects that could be attached to the owner’s belt with a knot, but their wrappers were not meant to protect the book. The wrapper seen in Fig. 11 leaves much of the book exposed to the elements. This book was made in the very late sixteenth century, when the production of girdle books was in decline. By then its protective function may have have been replaced by fashion: exposure – being seen with a book – may well have been what the owner was after. There was a price to pay, however, as the book is too large and heavy to carry around with convenience. In fact, attaching this object to your belt may have cause unwanted exposure as well: there was a good chance the book’s weight brought down your pants.

Postscript: this older post shows how medieval texts moved through Europe and how you can tell from barely-visible marginal notes.

That’s nice to hear!

LikeLike

The care and devotion given to these medieval “book bags” puts my canvass library bag to shame.

Your blog never ceases to amaze and inspire.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on συμποσίον ἀκταῖος κατακηλέω.

LikeLike

You are most welcome!

LikeLike

just wonderful to see ..thank you

LikeLike

This is very interesting. I find the idea of a sort of leather netsuke quite charming.

LikeLike

You’re welcome. Thanks for visiting!

LikeLike

fascinating, thank you.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Books I've Enjoyed (and some I haven't).

LikeLike

Thanks for your remark. With at least 2-3 kilos the book is much too heavy to conveniently attach to your belt, even if it could support its weight. I must admit, however, that the last line was prompted by a fun way to end the post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your tag line is amusing, as it is meant to be; but you appear far too well-informed and thoughtful an observer of these periods not to be aware that the chance of someone’s “pants” (already an anachronism) being brought down is highly unlikely to impossible: the lower extremities were clothed in hose, tied to the upper garment by laces…and the girdle-book would have been supported by…a girdle (belt) separate from either garment. what Would I be worried about? — Bruising (or worse) in the regions below the waist…

LikeLike

Could you explain what you mean – I am unfamiliar with the term.

LikeLike

Very interesting. Have you examples of a fasciculus?

LikeLike