This is the first post of my new blog medievalbooks.nl. Until now I have posted short blogs on my Tumblr and longer ones on the collaborative research blog MedievalFragments. As the latter will be coming to an end, this is a good moment to start a blog with longer posts of my own.

Artisans

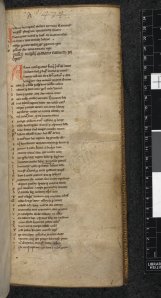

The most “in your face” clue about the individuals who produced the manuscript is provided by the script – the handwriting of a medieval scribe. As you start reading the first page, certain book-historical data starts to flow. The shape of medieval letters transmits two important pieces of information: the scribe’s whereabouts and “whenabouts”. I have blogged about the peculiar process of “sensing” how old a manuscript is (read it here). A similar feeling produces a sense of the country or region where the scribe was trained – and where he, we presume, produced the book. This copy of William of Conches’ Dragmaticon philosophiae (Fig. 1) was clearly produced by a scribe trained in Southern France. Such is suggested, among other things, by the shape of Tironian “et”, which features a firm and long horizontal top that starts far left from centre (Fig. 2).

In fact, according to this British Library record François Avril placed the manuscript in Languedoc, in the very south of France. He did so on the basis of the decoration, which is another bookish feature expressing information about the origins of a manuscript. Both the colours of the initial and the “box” placed around it have a Southern-French feel (Fig. 3), showing that both artisans – scribe and decorator – were likely trained in that region. Decoration is a key element in the pursuit of information about the makers of a manuscript. This, in turn, increases the value of the opening page, because many medieval manuscripts (including the one shown in Fig. 1) contain a decorated initial on their first page only. The start of the book had to be celebrated, as it were, providing us with clues as to where that party took place.

Owners

The first page is even more important for establishing who owned the manuscript. We often forget that the average medieval book may have had as many as fifteen owners. A thirteenth-century copy, for example, is currently 800 years old. If the average reading life of an individual was forty years (meaning he started to build a library at, say, twenty years of age), we may assume that the thirteenth-century book in question has had twenty different owners. It is no surprise, then, that we often find multiple names and ex-libris inscriptions written down in medieval books.

The first page was a prime location for such details, in part because medieval librarians knew that ownership inscriptions placed on cover- and flyleaves would disappear when the book was rebound. British Library, Sloane MS 2424 features a wide array of ownership inscriptions on its opening page, both from medieval and modern times. The oldest one is found at the very top: an ex-libris inscription in thirteenth-century cursive script (Fig. 4). It is partly erased (as one does with second-hand books), meaning the identity of the institution who owned the manuscript remains anonymous.

The page in question also holds more modern shelfmarks. The number “2424”, written down in an eighteen-century hand, refers to the book’s place in the library of Sir Hans Sloane (d. 1753), who owned the manuscript prior to the British Library (Fig. 5). An earlier shelfmark, “B.27”, scratched out by Sloane, was likely from one of the previous owners – which included Louis Malet and Sir Robert Cotton, as the Schoenberg Database of provenances tells us. A nineteenth-century stamp from the British Library points to the present owner.

Purpose

The hardest thing to read from the first page of the medieval manuscript is the purpose for which the object was made. For this kind of information one may turn to dimensions and layout. The pretty manuscript in Fig. 6, for example, has margins that are slightly wider than normal. Originally the margins would have been even larger, considering that the book was bound at least twice, meaning that its width was reduced twice by the binder’s knife. Such broad margins suggest that this twelfth-century book filled with patristic excerpts was designed to be glossed. In fact, a later user did use the provided space for his (illegible) personal notes.

As with layout, a page’s dimensions may also provide information about the purpose for which a medieval book was created. Take the peculiar copy of Virgil’s Aeneis in Fig. 7. The book breaks with the norm of medieval book production in that the page is extremely high and narrow. We know that this format was favoured by individuals who used books in a setting of performance, such as soloists in the church and actors on the stage. Similarly, teachers in monastic schools enjoyed the narrow format, which accommodated their walking through the classroom as Virgil’s text was used to teach novices Latin grammar – a common use for classical manuscripts in this age. In sum, the likely function of Harley 2777 already jumps off its first page.

For the impatient scholar who cannot wait to see the first page, narrow books like the Harley Virgil are perfect. After all, its unusual dimensions, which are so very telling for the manuscript’s purpose, are already evident when the manuscript is still sitting in its box, unopened. Even before the first page is consulted, the manuscript has already transmitted some of its secrets.

Note – You may want to check out the accompanying post devoted to the manuscript’s ‘last’ page, which was published on my project’s collaborative research blog MedievalFragments. It is reposted below (or click here).

Thanks for your interest – and glad you like the blog. I have no time, unfortunately, to increase my blogging frequency. Thanks for offer!

LikeLike

Greetings! I know this is kinda off topic but I’d

figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in trading links or maybe guest

writing a blog post or vice-versa? My site discusses a

lot of the same topics as yours and I think we could greatly benefit from each other.

If you might be interested feel free to shoot me an email.

I look forward to hearing from you! Awesome blog by the way!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Writer's Cramp and commented:

This is the first post in a very interesting blog started in August on medieval books.

LikeLike

Thanks – and also for letting me know!

LikeLike

I do so too, but blogging keeps me focused on my work, in a strange way.

LikeLike

WordPress works well for me because it is easy to use. With minor financial investment you can make “wordpress” disappear from the URL. It’s worth it, I think. For aspiring bloggers: just start blogging and you’ll find your voice.

LikeLike

Wonderful blog! Do you have any helpful hints for aspiring writers?

I’m planning to start my own blog soon but I’m a

little lost on everything. Would you suggest starting with a free platform like WordPress

or go for a paid option? There are so many options out there that

I’m completely confused .. Any ideas? Cheers!

LikeLike

Aw, this was a really nice post. In thought I want to put in writing

like this moreover ཿ taking time and precise effort to make a very good article

but what can I say I procrastinate alot and under no circumstances appear to get

something done.

LikeLike

Hey very nice blog!

LikeLike